Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958) was an African-American journalist, teacher, playwright and poet who was part of the Harlem Renaissance and was one of the first African-American women to have a play performed. Born in Boston, the daughter of Archibald Grimke, a prominent journalist who served as Vice-President of the NAACP. The Grimkes were a prominent biracial family whose members included both slaveowners and abolitionists. Two of her great aunts, Angelina and Sarah, were prominent abolitionists in the North. Angelina Weld Grimke was named after her aunt who had died the year before.Her paternal grandfather was their brother Henry Grimké, of their large, slaveholding family based in Charleston, South Carolina. Their paternal grandmother was Nancy Weston, an enslaved woman of European and African descent, with whom Henry became involved after becoming a widower. Grimke’s mother, Sarah Stanley Grimke, a white woman, left her husband under the influence of her parents who never approved of her interracial marriage, and took her three-year old daughter with her. However, at the age of seven, Angelina was returned to her father, and although she and her mother corresponded, they never saw one another again. Sarah Stanley died of suicide several years later.

Grimké wrote essays, short stories and poems which were published in The Crisis, Opportunity, The New Negro, Caroling Dusk, and Negro Poets and Their Poems. Some of her more famous poems include, “The Eyes of My Regret”, “At April”, and “Trees”. She was an active writer and activist included among the figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Her poetry dealt with more conventional romantic themes, often marked with frequent images of frustration and isolation. Recent scholarship has revealed Grimke’s unpublished lesbian poems and letters; she did not feel free to live openly as a gay woman during her lifetime.

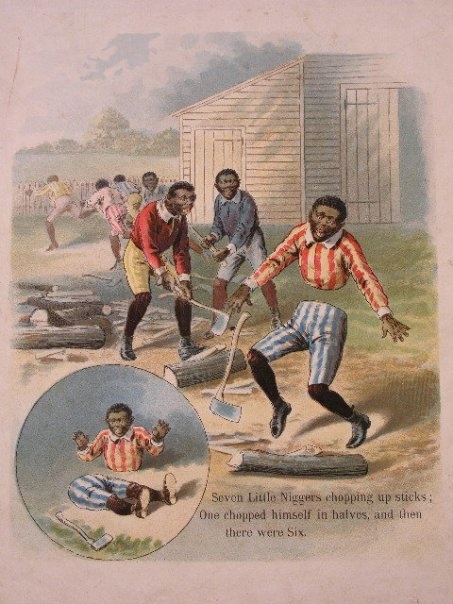

Grimké also wrote a play called Rachel, one of the first plays to protest lynching and racial violence. She wrote the three-act drama for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to rally public support against the recently released film The Birth of a Nation. The play was produced in 1916 in Washington, D.C., performed by an all-black cast. It was published in 1920.

After her father died, Grimké left Washington, DC, for New York, where she lived a reclusive life in Brooklyn. She died in 1958 after a long illness.

http://www.aaregistry.com/detail.php?id=1123

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angelina_Weld_Grimké

[b. 1914 – d. 1965]

[b. 1914 – d. 1965]

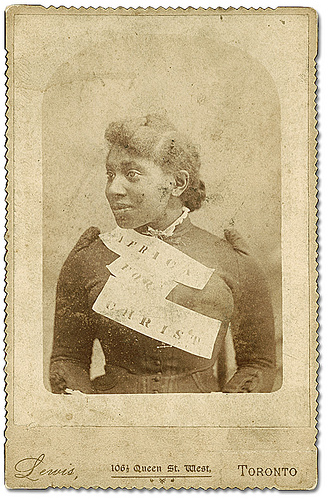

sash reads “Africa for Christ”

sash reads “Africa for Christ”