Seeing as this is byeracial blog, it’s about time I posted about hair. Not my own. I really do love my hair and I suppose it’s the one physical characteristic that gives a clue as to “what I am.” Nothing more interesting to report on that. However, this article below is much more about identity and not having a culture to fall back on than it is about curls and that is interesting to me. More often than not, when you’re mixed, you really don’t have that soft place to fall. The mixed experience has historically been ignored, making it nearly impossible to forge a cultural identity. Good news: We have the opportunity to transcend attachment to a cultural identity. Bad news: This leaves us at the whim of the cultural identities projected onto us.

RACE AND NATURAL HAIR- “YOU’RE MIXED SO YOU DON’T REALLY KNOW THE STRUGGLE.”

About a year ago, I wrote an article about how much I disliked being mixed because of my hair. These last few months, I realized that I didn’t embrace the natural hair life because of others and not me. I liked my curls and had already transitioned not knowing it. I still didn’t accept the fact that my curls were acceptable. In my mind, straight hair was the ideal. To be honest, I didn’t really know how to take care of my hair yet but the main reason I thought this was because of negative comments. Comments such as…”You should relax your hair again.”, “Your hair looks messy all the time.”, and the last and most important one was…”You need to stop trying to look black”. They always ended up going back to that one.

About a year ago, I wrote an article about how much I disliked being mixed because of my hair. These last few months, I realized that I didn’t embrace the natural hair life because of others and not me. I liked my curls and had already transitioned not knowing it. I still didn’t accept the fact that my curls were acceptable. In my mind, straight hair was the ideal. To be honest, I didn’t really know how to take care of my hair yet but the main reason I thought this was because of negative comments. Comments such as…”You should relax your hair again.”, “Your hair looks messy all the time.”, and the last and most important one was…”You need to stop trying to look black”. They always ended up going back to that one.

The race topic is one that strikes me the hardest when it comes to my hair. Many people believe that natural hair is just for blacks. They forget that the world is not simply made of blacks and whites. Many cultures and races have mixed. The end result of that is people like me. People who share features of both races or may only have features of one but who feel attached to both. I am a born and raised Dominican. If you spend a lot of time with Latinos or Dominicans, you will quickly realize that we believe we are a different race. It’s actually very confusing because there are a lot of forms that will have Hispanic/Latino as a choice for race and not for ethnicity. A lot of people will tell you that Latinos are not a separate race. This doesn’t stop us from feeling that way. The problem with this is that even though they have a lot of african heritage as well as native american heritage…they refuse to acknowledge it. It’s not a lack of education, but a lack of acceptance.

So what does this have to do with hair? If you’re black or if you’re Latino, you were most likely raised hearing negative comments about your hair. Now, you might be saying…”Well, I know. What’s your point?”. My point is that I didn’t have one or two races/ethnicity telling me I looked undesirable, I had three. This had an impact on how I felt about myself. Even though black naturals may get a lot of crap from relaxed hair women or women who naturally have straight hair… they still have natural sistas. I had and some times still don’t have a culture to really fall back on and say…”You understand what I’m going through”. The reason is that my skin is white and my physical features are mostly European. My hair is pretty much the only thing that lets you know that I’m mixed. This causes a problem because white people expect an image of me that I don’t quite complete, black people expect an image of me and Latinos/Dominicans expect a certain image of me. In comments and forums, I have received things like “Well, you’re mixed so you don’t really know the struggle”. In school, I was told my fro was a distraction (I never told anyone that). In the streets, I’ve been told…”Your skin is far too fair for you to wear your hair like this”(it was in a fro). You can take a guess at which races/ethnicity said each.

What I would like is for women to realize that you can’t really know someone else’s “struggle”. Relaxed women and natural women should stop trying to debate about what is the right choice, because guess what? It’s a personal choice. This also applies for big choppers and transitioners. It would also be nice if business people realized that curly/kinky hair doesn’t reduce our ability to work effectively. The last but the most is important is that I would like for people of all races to realize how much it hurts to be pushed away because of your skin color or your features. Usually when people think of racism, they think of whites against the minorities. The thing that most don’t realize though is that we judge each other just as much as other races do.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

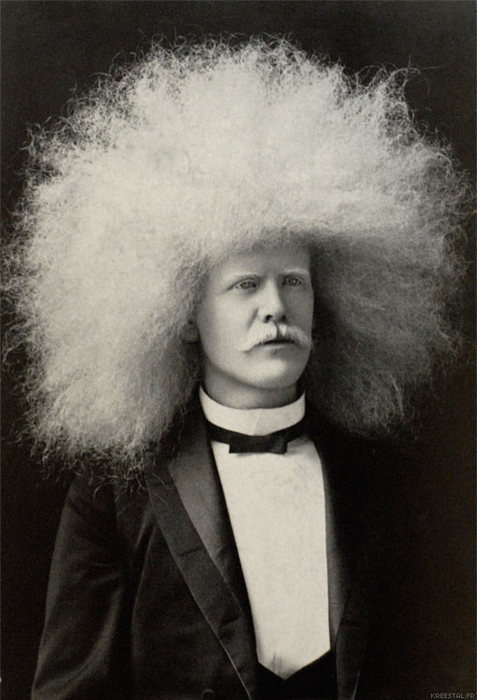

And to include the boys…Something about the commentary on this photo of Pete Wentz reeks of nappy headed-ho…😡

white man afro: Pete Wentz ditches his straightener, looks unrecognizable

After a seemingly life-long love affair with his hair straightener, Pete Wentz has debuted a more natural, afro-esque head of hair. Gasp!

The emo rocker was launching a a new car or something, no-one knows for sure – all eyes were on his frizzy head pubes.

We’ve got to give the guy credit – he managed to get that thing poker-straight every day for years!