Christia Adair (1920)

In 1920, Christia Adair took some schoolchildren to meet the train when Republican Warren G. Harding was campaigning for the presidency. After seeing him shake hands only with the white children, she became a Democrat.

***************************************

[b.1893 – d.1989]

Christia Adair was a teacher, a community leader, and a tireless activist for the rights of women and African-Americans. Born in Victoria on October 22, 1893, Adair spent her early years in Edna, then moved to Austin with her family in 1910. She attended college first at Samuel Huston (now Huston-Tillotson University) and then at Prairie View Normal and Industrial College (now Prairie View A&M.) After graduation she moved back to Edna, where she taught elementary school.

She married Elbert Adair in 1918, and they moved to Kingsville. There she opened a Sunday school, and also began her community activism. She joined a multiracial group opposed to gambling, and then became involved in the suffrage movement. At that time neither blacks nor women could vote, and anyone who knows her feminist history knows that there was some racism in the suffrage movement. Indeed, after the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, blacks were still turned away from the polls because of racist whites’ tactic to deter them: the white primary. Since the South was wholly Democratic at that point, the primary basically decided the election. Thus excluding African-Americans from the primary effectively disenfranchised them. Adair had this to say:

“Back in 1918 Negroes could not vote and women could not vote either. The white women were trying to help get a bill passed in the legislature where women could vote. I said to the Negro women, “I don’t know if we can use it now or not, but if there’s a chance, I want to say we helped make it.

“We went to the polls at the white primary but could not vote…We kept after them until they finally said ‘You cannot vote because you are a Negro.'”

This was a smart strategy, because that gave them grounds to sue. And sue they did. The Adairs had moved to Houston in 1925, and Christia had become very active in the Houston chapter of the NAACP. As executive secretary, she was a driving force behind the landmark lawsuit, Smith v. Allwright, which overturned the white primary – and helped set the stage for Brown v. Board of Education.

In the Jim Crow South, these activities made Adair and her colleagues targets for racist whites. The chapter received bomb threats with alarming regularity. The Houston police were not helpful. In fact, they were a hindrance. According to Adair’s entry at the Handbook of Texas Online:

In 1957 Houston police attempted for three weeks to locate the chapter’s membership list. While the official charge was battery – the illegal solicitation of clients by attorneys – Adair believed the real purpose was to destroy the organization and its advocacy of civil rights. She testified for five hours in a three-week trial over the attempted seizure of NAACP records. Two years later, on appeal to the Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall again won a decision for the organization. Adair never admitted having membership lists or having member’s names. In 1959 the chapter disbanded and she resigned as executive secretary, though she later helped rebuild the group’s rolls to 10,000 members.

Now that’s a hardcore sister. And she didn’t stop there. She was a lifelong leader in the Methodist Episcopal Church and a precinct judge for more than 25 years. She also helped to…

* desegregate Houston’s public buildings, city buses, and department stores

* win Blacks the right to serve on juries and be considered for county jobs

* convince newspapers to refer to blacks with the same courtesy titles used for

whites

* desegregate the Democratic Party in Texas

Any one of her achievements is impressive. Taken together, they’re downright amazing. And folks noticed. Adair was recognized by many for her brave and principled activism. Zeta Phi Beta sorority named her Woman of the Year in 1952. In 1974 Houston NOW honored her for suffrage activism. In 1977 she was selected as one of four participants in the Black Women Oral History Project, sponsored by the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College. That same year the city of Houston named a park for her. And in 1984, she was named to the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame. Adair died just a few years later at the age of 96, on New Year’s Eve 1989, leaving behind her an indelible legacy of justice and equality.

Above bio from: NOW National Organization for Women

Photo and paragraph directly below photo from: ‘The Face of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial America to the Present’ edited by Kathleen Thompson and Hilary Mac Austin

http://www.flickr.com/photos/22067139@N05/3395503109/

WOW!!! Such an important woman. How had I not heard of her before? Thank you, Omega!

City Councilman Bill Boyd began with a genealogy quest, but unearthed a love story worthy of Rhett and Scarlett and an eventual demise worthy of Jimmy Hoffa.

City Councilman Bill Boyd began with a genealogy quest, but unearthed a love story worthy of Rhett and Scarlett and an eventual demise worthy of Jimmy Hoffa.

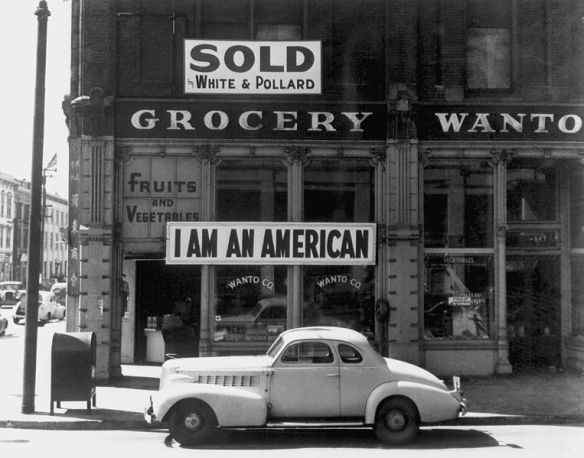

September 4, 1937:

September 4, 1937: