Speaking of cartoons…

While researching Jackie Ormes I somehow found my way to the ListVerse 10 Great Female Cartoon Voice Actors. I was so pleased to see Lillian Randolph as number one. I was not aware of Lillian Randolph beforehand. I was honestly just glad to see a woman of color on the list, not to mention at the top of it. Biracial Cree Summer is also on the list. Anyway, my pleasure was kind of short-lived when memories of Mammy Two-Shoes resurfaced.

I loved Tom & Jerry as kid. I remember watching it in the morning before school. Any racial overtones/offenses were lost on me at the time. But as an adult watching that cartoon, I have been shocked by the appearance of Mammy Two-Shoes. In my opinion it looks like Mammy Two-Shoes has paws for hands, but maybe that’s just how they draw hands.

From ListVerse: http://listverse.com/entertainment/10-great-female-cartoon-voice-actors/

Lillian Randolph

Lillian Randolph(December 14 1898-September 12 1980) was an African-American actress and singer, a veteran of film, radio and television. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, she was the younger sister of actress Amanda Randolph.

She worked in entertainment, from the 1930’s well into the 1970’s, appearing in hundreds of short subjects, radio shows, motion pictures and television shows. Randolph is best known as the maid Birdie Lee Coggins from “The Great Gildersleeve” radio comedy and subsequent films and television series, and as Madame Queen on the “Amos ‘n’ Andy” television series from 1951 to 1953. Her best known film role was that of Annie in “It’s a Wonderful Life.” She appeared in several featured roles on “Sanford and Son” and “The Jeffersons” in the 1970’s.

Her most profilic acting role, hoever was her uncredited voice-over part as Mammy-Two-Shoes in William Hannah and Joesph Barbara’s “Tom and Jerry” theatrical cartoon series for Metro Goldwyn Mayer during the 1940’s and early 1950’s. Randolph made a guest appearance on a 1972 episode of the sitcom “Sanford and Son” as Hazel, a distant relative of the Fred Sanford character.

In the Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940’s and 50’s, the only human character was an unnamed lady who was always after Tom (originally named Jasper), a cat, to catch Jerry, a mouse. Radio and film veteran Randolph provided the voice. The character is considered to be a racial stereotype known as a “Mammy”, a servant or maid of African descent, often overweight, loud, and heavily accented, and this has lead to some controversy. The shorts though, never stated that she was a maid and it is implied that she was the owner of that huge house with the well-stocked refrigerator. Also, the name “Mammy Two Shoes” was never used in the cartoons; it was given years later by the media, as typically only the character’s feet were shown. The shorts would be edited in the 1960’s. In some, Randolph’s voice was replaced with a plain-sounding one, and in others, she was replaced entirely with a thin white woman (voiced by June Foray.) Recent DVD releases have somewhat restored the original character.

From http://mammytwoshoes.tripod.com/history.html

By the early 50’s, Mammy was a supporting character just as important as Spike or Nibbles. However, in 1954, the Supreme Court declared racisism unconstitutional, which took a great affect on Hollywood movies and cartoons. So Mammy was forced to retire in 1952’s “Push-Button Kitty”. The new law pressured MGM to reissue the cartoons with her in them. The “White Mammy Two-Shoes” versions were created back in the 1960s for CBS when they were airing these cartoons. The work was done by Chuck Jones’s crew when Jones was making new Tom and Jerry theatricals. I recall reading Chuck’s remarks that at the time MGM still had most of its old animation artwork on file, so it was pretty much just a matter of retracing and repainting the original pencil animation and photographing it against recreated backgrounds. This new “White Mammy” material was then cut into dupe negatives of the cartoons in question to replace the original “Black Mammy” footage. Voice actress June Foray was brought in to redub the soundtracks. (Incidentally, that voice is supposed to be Irish.) Instances where the “White Mammy” has a “Black Mammy” voice (or vice versa) is a result of carelessness. Picture and sound elements on film masters are stored separately. What happens is simply that someone isn’t paying attention and matches a newer “White Mammy” picture element to the original “Black Mammy” sound element (or vice versa).

Click here to hear mammy two-shoes http://mammytwoshoes.tripod.com/sounds/mousecatcher.wav

September 4, 1937:

September 4, 1937:

[b. 1914 – d. 1965]

[b. 1914 – d. 1965]

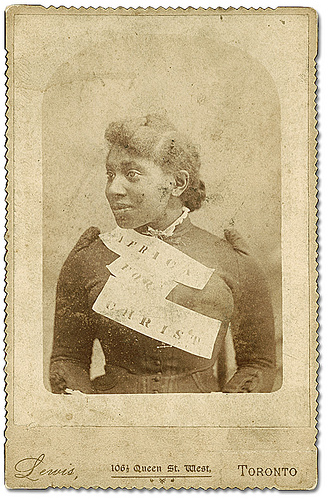

sash reads “Africa for Christ”

sash reads “Africa for Christ”