This article is from 2005. I wonder if the family has noticed a shift in attitudes over the last five years. And of course I’d love to hear from little Toni. The bridge between them. I like that part a lot.

HOW DARE THEY TREAT US LIKE THIS?

by DIANA APPLEYARD

JAN LLOYD, 45, has been married to Tony, 48, for ten years. The couple have a four-year-old daughter, Toni. They run a successful martial arts business, Fighting Fit, with gyms around South London, where they live.

photo by Jenny Goodall

Jan says:

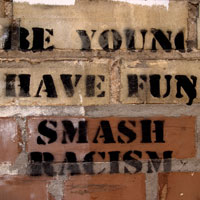

PEOPLE have spat at me in the street, stared at me, jostled me and shouted at me — all because I fell in love with a black man. But unless you have experienced it, you are unlikely to have any idea of the racism in British society.

It’s terrifying, but it’s something I am aware of every day of my life. We were taking our daughter Toni to see the GP when she was only two years old, when I was spat at in the street. It was completely random — a white man in his 40s looked us up and down and then spat at me.

It was so disgusting — I couldn’t believe it was happening. I looked for support, but everyone looked away. They were embarrassed and probably disgusted too, but no one wanted to get involved. I was shaking and tearful, but angry as well — how could someone behave like that in a civilised society?

As I walk down the street, go to the pictures, eat out in restaurants or go to the theatre, I am frequently aware of a kind of coldness and embarrassment around me. The only way I can describe it is that it’s like being disabled — people don’t know how to treat you.

They don’t know what to say to me. You can see the thought running through people’s minds: ‘Why is she with a black man?’

When I got together with Tony, a lot of my friends melted away. They’d invite me to a party with my new boyfriend, but then, mysteriously, they’d never invite us again. Once, early in our relationship, I’d booked a table at a nice restaurant. When we arrived, there were lots of empty tables — but they put us at the back, next to the toilets. I was going to complain, but Tony told me just to leave it. He’s used to it. Our backgrounds could not be more different. I was brought up in a well-off family in Sussex and was privately educated. I met Tony when I took up aerobics and he was my instructor. I thought he was nice, but our relationship didn’t progress until I was in a horrid road-rage incident, when a man hit my car and then bashed on my window. It made me realise I ought to learn self-defence and Tony also taught martial arts. Before I fell for him, I’d been out with City types, public-school educated white men, so Tony was a real change. I thought he was intelligent and interesting — I was fascinated by the fact that his life was so different from mine.

He was born in Yorkshire, but his family moved to London when he was three. He had traditional values and an old-fashioned approach to relationships. There was also a lovely warmth about him. He was successful and welloff through his business and he was a real self-made man.

We started going out and six months later I met his family. He’s one of six and it was so different from my middle-class home — they were so loud, so welcoming, pressing food on me and firing questions at me.

Tony told me he’d been badly beaten up as a child by racist bullies and that nearly every day he faced some kind of prejudice or abuse — it hurt him so much.

But it wasn’t long before I started to experience the kind of hostility he’d faced most of his life. Suddenly, being with him, I was made to feel like a freak, a secondclass citizen. It was bizarre. There was so much disapproval in people’s glances. There seems to be this attitude like ‘Aren’t white men good enough?’ when all I had done was fall in love.

We had been together only six months when we decided to get married and it came as a shock to my parents, who asked me if I was sure it was going to work given our cultural backgrounds. But they have since mellowed and little Toni is the bridge between us.

My parents are very traditional, and all they could see were problems in a mixed marriage.

We married on a beach in St Lucia. Both sets of parents came and it made such a difference being there — we were surrounded by welcoming black people, and my parents felt less uneasy. Now they are very supportive of Tony and can see what a good man he is. Before, they — like so many others — had only seen the stereotypes.

After our wedding I joined Tony in his business, and Fighting Fit is now very successful. We live in a lovely four-bedroom house, we enjoy great holidays, scuba dive, ride horses and have a happy, middle-class life. Now when I get the looks, I ignore them and carry on. They can’t harm our life or family.

I did worry a little about our daughter and whether she’d face any prejudice at school being mixed race, but she’s totally accepted — she’s just Toni, with a big personality for a little girl, so sunny and confident. Everyone loves her.