I’ve been sucked into the Civil War on the great interweb today. Haven’t even watched Glory yet. I’m so fascinated by this history. Most of the photos and information in this post were found on one of Life Magazine’s photo galleries dedicated to the Civil War. I must say that I would bet money that the man in the photo entitled Ready to Fight is a mulatto. To call him biracial for the sake of political correctness would not be historically accurate, and sounds as preposterous to me as do all of the captions claiming that “African Americans” are depicted in the photos. White folks of the day had a difficult enough time even agreeing that they were human beings… 3/5ths of a person… That’s one of the reasons that I currently hate to use that terminology. We don’t go around being so specific with Irish Americans, or Italian Americans, or German Americans. Still seems like some 3/5ths mentality to me. That is just my opinion though. I am also of the opinion that the difference between what was going on in the Union Camp in the photo entitled At Your Service and the goings on in the Confederate camp photo titled Off the Clock is… absolutely nothing. Contrary to popular youtube belief, I am not one of those Yankees who thinks that the Union and President Lincoln were perfect and had nothing but the best of intentions for black people. Nor am I under the impression that if I dug back far enough in my family tree, I would find abolitionists and/or soldiers fighting for the North. Quite the contrary, I’m almost positive. That’s why my existence is a miracle! Of course everyone’s is, I’m just sayin’… today… in light of this complex history… how did I even happen?

![[Nick+Biddle.jpg]](https://mulattodiaries.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/nick2bbiddle.jpg?w=339&h=505)

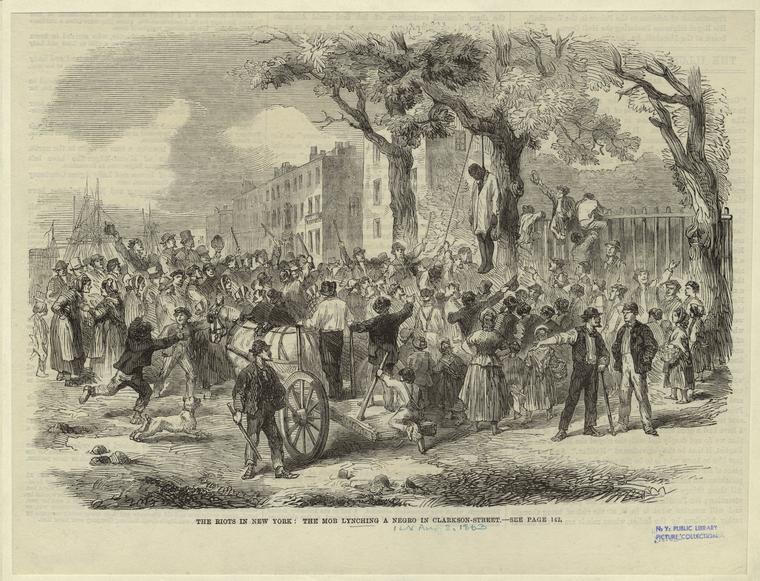

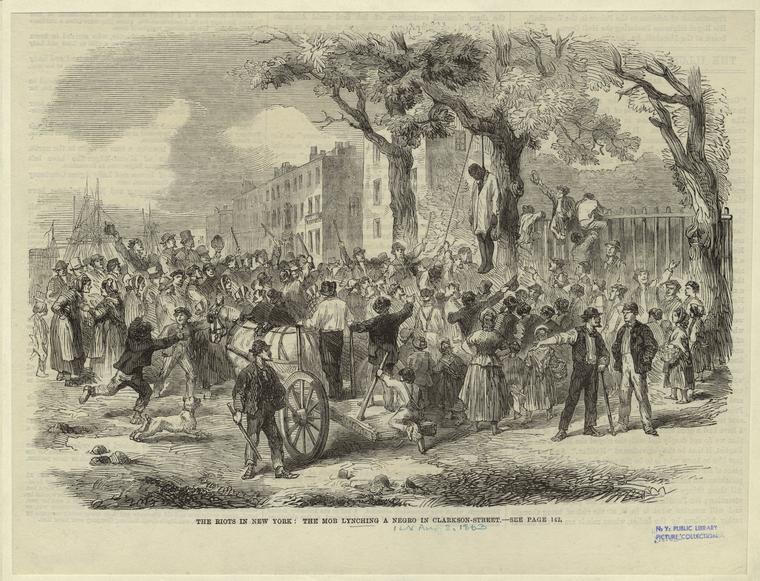

First Blood

Even before blacks were officially recognized as federal soldiers, many slaves — including the man in this portrait, known as Nick Biddle — escaped and joined Union lines. In 1861, Biddle was the orderly of a white Pennsylvania militia officer and, wearing a uniform, traveled with his employee’s company to Baltimore to help protect Washington, D.C., after the surrender of Fort Sumter. Once there, he was set upon by a pro-Confederate mob, attacked with slurs and a brick that hit him in the head so severely it exposed his skull. Some consider him the first man wounded in the Civil War.

VIA

The Grave of Nick Biddle:

By Chaplain James M. Guthrie

The grave of Nick Biddle a Mecca should be

To Pilgrims, who seek in this land of the free

The tombs of the lowly as well as the great

Who struggled for freedom in war of debate;

For there lies a brave man distinguished from all

In that his veins furnished the first blood to fall

In War for the Union, when traitors assailed

Its brave “First Defenders,” whose hearts never quailed.

The eighteenth of April, eighteen-sixty-one,

Was the day Nick Biddle his great honor won

In Baltimore City, where riot ran high,

He stood by our banner to do or to die;

And onward, responsive to liberty’s call

The capital city to reach ere its fall,

Brave Biddle, with others as true and as brave,

Marched through with wildest tempest, the Nation to save.

Their pathway is fearful, surrounded by foes,

Who strive in fierce Madness their course to oppose;

Who hurl threats and curses, defiant of law,

And think by such methods they might overawe

The gallant defenders, who, nevertheless,

Hold back their resentment as forward they press,

And conscious of noble endeavor, despise

The flashing of weapons and traitorous eyes

Behold now the crisis—the mob thirsts for blood:-

It strikes down Nick Biddle and opens the flood—

The torrents of crimson from hearts that are true—

That shall deepen and widen, shall cleanse and renew

The land of our fathers by slavery cursed;

The blood of Nick Biddle, yes, it is the first,

The spatter of blood-drops presaging the storm

That will rage and destroy till Nation reform.

How strange, too, it seems, that the Capitol floor,

Where slaveholders sat in the Congress of yore,

And forged for his kindred chains heavy to bear

To bind down the black man in endless despair,

Should be stained with his blood and thus sanctified;

Made sacred to freedom; through time to abide

A temple of justice, with every right

For all the nation, black, redman, and white

The grave of Nick Biddle, though humble it be,

Is nobler by far in the sight of the free

Than tombs of those chieftains, whose sinful crusade

Brought long years of mourning and countless graves made

In striving to fetter their black fellowmen,

And make of the Southland a vast prison pen;

Their cause was unholy but Biddle’s was just,

And hosts of pure spirits watch over his dust.

Ready for a Fight

A black soldier poses with his revolver in 1865. Many military leaders didn’t believe African Americans were capable of fighting effectively at first, but battles including the one at Port Hudson…proved them wrong.

Mulatto Confederate Soldier Daniel Jenkins and his wife. Jenkins was with the Confederate 9th Kentucky Infantry and was killed at Shiloh on 4/6/62.-VIA

Off the Clock

Confederate soldiers at their campsite play poker, while drinking and smoking between battles, with two slaves serving them.

At Your Service

Four white Union soldiers sit outside their tents at Warrenten, Va., as an African American soldier hands a bottle and a plate of food to one of them, in 1862.

Women in the War: Mary Walker, American Hero

Caption: Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919), US Civil War doctor, wearing her Medal of Honor in 1866. Walker was awarded the medal in November 1865 for her service in the US Civil War (1861-1865). She served in the Union Army in several battles, first as a nurse and later as the first-ever female US Army Surgeon. She was captured in April 1864 by Confederate forces and accused of spying, though she was later released. After the ordeal, the government awarded Walker the Medal of Honor for her bravery, the only woman to ever given such an honor. After the war, she was involved in the temperance movement and the women’s rights movement. She would often wear men’s clothes, and campaigned for dress reform for women. This photograph is from the Matthew Brady Collection, a collection of photographs from during and after the US Civil War.

Caption: Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919), US surgeon. Walker received her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. During the US Civil War (1861-1865) she served as the first female surgeon in the US Army. She was awarded the Medal of Honour for her wartime service, an award revoked in 1917 and restored in 1977. Walker also campaigned on women’s rights and suffrage, and was well-known for wearing male dress, including a top hat. This photograph dates from between 1911 and 1917. It is from the Harris and Ewing Collection, which mostly consists of photographs taken in Washington DC, USA.

War Orphans Used in Propaganda

An African American brother and sister, both former slaves, pose for a photograph after being freed by Union soldiers in Virginia in 1864. The children’s mother was beaten, branded, and sold at auction because she had been kind to Union soldiers.

Free Children

The same brother and sister are photographed after having been sent to an orphanage in Philadelphia.

Jumping Ship

In some cases, having blacks in their ranks worked against the South, as with Robert Smalls, a slave forced to serve in the Confederate Navy (which permitted slaves to serve with their masters’ consent — technically so long as African Americans made up no more than 5 percent of the crew). Smalls took over his CSA ship and delivered it to Union forces, became a ship pilot in the U.S. Navy, and rose to the rank of captain. Smalls…later became a member of the South Carolina State House of Representatives.

Slavery Lasted Longer in the Union Than in the Confederacy

Slavery technically existed in the North longer than it did in the South, as the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation only applied to the states that had seceded. The Union slave states of West Virginia, Maryland, and Missouri abolished slavery during the war. Kentucky and Delaware, however, continued allowing slavery until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States in December 1865.

New York City Considered Seceding From the Union

Though New York is viewed by much of America as the emblematic Northern city, it was actually a hotbed of pro-South and anti-war sentiment before and during the Civil War, not least because the city thrived on trade with cotton plantations. In January 1961, Mayor Fernando Wood even tried to convince the City Council to officially secede from the Union and declare itself a neutral city-state. Anti-war feelings crested with the bloody Draft Riots in July 1863, when working-class New Yorkers went on a rampage to protest new laws Congress passed to institute a draft.

The Great Emancipator Rejected Emancipation at First

Though he’s now lauded as the man who freed the slaves, President Abraham Lincoln was routinely lambasted by the abolitionists of his time for not moving fast enough or far enough in ridding the country of the institution of slavery. When the Emancipation Proclamation finally was issued, it exempted the Union border states, Tennessee, seven counties of Virginia, New Orleans, and 13 Louisiana parishes. It also implicitly offered Southern secessionist states a chance to keep their slaves if they rejoined the Union by Jan. 1, 1863.

![[Nick+Biddle.jpg]](https://mulattodiaries.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/nick2bbiddle.jpg?w=339&h=505)