Here are excerpts from two stories similar to the one I posted yesterday. You can read them in their entirety HERE.

Her Father’s Daughter

Cindy Foster will never forget the face in the window.

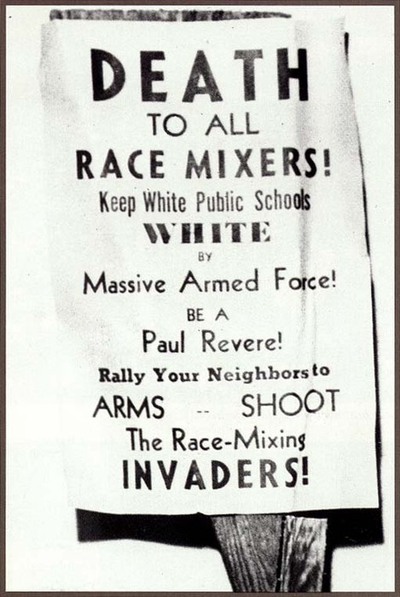

She woke up in the middle of the night, sat up in bed, and saw a man — she believes it was a white man — peering through her bedroom window. It was the early 1960s in a small Alabama city, and her family had just received a bomb threat from the Black Panthers because of her father’s notoriety as a Klan leader.

Foster, then about 6, tried to scream for help but her voice failed. Then the face disappeared. She later found out it was probably an FBI agent checking on her family’s safety.

The midnight memory is just one example of how her late father’s Klan activities cast an uneasy shadow over her childhood. The family received other threats; she recalls long stretches of wariness punctuated by moments of fear. That legacy continued to haunt her as an adult. She suffered from nightmares, was constantly vigilant, and didn’t easily trust others. She saw a therapist for several years and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety condition that can develop after frightening events. And she struggled to assert her own identity in the hometown where nearly everyone knew who her father was and assumed she shared his views about race.

“I just wanted to be me — not my father’s daughter,” said Foster, who now lives in northern Florida. (The Intelligence Report agreed not to identify her father, who died in 2003, to protect Foster’s privacy.)

In fact, Foster held beliefs very different from her father’s — a phenomenon she attributes partly to her faith. As a child of about 4 attending Sunday school in her family’s Methodist Church, she sang that Christ’s love is colorblind: “Jesus loves the little children/all the children of the world/black and yellow, red and white/They’re all precious in his sight.”

“I realized at a very young age that you either had to believe what the church taught or what my father stood for,” she said. “And what I saw my father doing was wrong.”

…Foster became a nurse, married and raised two children. For several years she volunteered as a Girl Scout leader, often working with black children from poor families. “I wanted to go out and do something for humanity and show that I believed differently than he did,” she said.

The Price of Hate

When Stephan Mills was 10 or 11, his father sat him and his older sister down after supper one night and told them that if they ever became emotionally involved with someone of color, he would kill them.

“I just nodded in agreement,” said Stephan, now 16.

The incident seemed normal to a boy who for years had been steeped in his father’s bigotry. Arthur Kemp, a South African white supremacist who has ties to British and American hate groups, indoctrinated his children with racist and anti-Semitic beliefs from the time they were very young. Stephan mostly adopted those views as his own. Several years ago, however, he rejected all that his father stood for. The experience would radically change his life and lead to his ongoing estrangement from his father, who’s now divorced from his mother and believed to be living in England.

“Stephan’s resentment toward his father is based partly on the fact that, in his sister’s words, he had to relearn to be a civilized human,” said his mother, Karen Mills.

There was a lot to relearn. Arthur Kemp “was a very involved and doting father” when his children were small, Karen Mills said. He read to them often, carefully choosing books he felt would reinforce his ideology. Among them were the original “Noddy” series, English children’s books that featured Golliwogs, dark-skinned caricatures that were later removed from the text because they were deemed racist. In one of Kemp’s favorite Noddy books, the Golliwogs steal Noddy’s car. Kemp enjoyed telling his children that the Golliwogs’ theft of the car amounted to typical behavior for blacks.

…He also forbade socializing with non-white children. If they arrived at a friend’s party to find that a black child had also been invited, Kemp made his children go home. When Stephan was six, his father reluctantly took him and his sister to swimming lessons at a public pool where one of the children turned out to be black. “He told us to get out and that we were leaving,” said Stephan, who now uses his mother’s maiden name. “I was still pretty young so I didn’t really understand what was going on.”

…He also relished showing them articles and statistics that purported to prove that blacks were inferior. He contended that blacks could never be race car drivers because they have poor depth perception, that they cannot swim because their bones are too dense, that they are not as intelligent because their brains are smaller.

“The children were actively encouraged to be vocal about their views and to challenge their peers,” Karen Mills wrote. “In Stephan’s case in particular, this resulted in him being ostracized and made an outcast as he followed his father’s lead.”

Stephan said he had few friends until his first year of high school. At times, he suffered from depression because his father’s brainwashing had so alienated him from his peers, his mother said.

“I wasn’t really someone that people wanted to hang around with,” Stephan said. “They regarded me as weird because I was constantly talking about Hitler.”

…Karen Mills said Kemp has had almost no contact with his children since their divorce. “I don’t think there’s any way that Arthur could fix the broken relationship with Stephan,” she said. Nonetheless, “Stephan has gone through something of a catharsis.” In addition to his posts on Lancaster Unity, he chose to discuss his father when he was assigned to give a school speech on someone who had influenced him — only he said his father’s influence had been entirely negative. Now, his social life is improving, and he has resolved to be as unlike his father as possible. “I am stuck with some of his traits and characteristics — Mom used to joke with me that I have the Kemp laziness gene — but definitely not his political views,” he said.

Yet there’s no bringing back the years he lost to his father’s hate. “You,” he wrote to him in the September 2008 Lancaster Unity post, “will never understand what you have done to me.”