Since I’ve been back on the blog, I have said very little about the so-called biracial experience. It amazes me that it’s still easier, even for me with all of my good “mixed” intentions, to talk about black and white. I forgive myself for this because without the black and white there is no mixed. Without the baggage of white vs. black stuff, there is no need for the mixed discussion. So, I suppose it’s only natural. It is little disappointing personally that the middle ground isn’t where the conversation begins for me. It’s on the ends of the spectrum. But I also suppose that this is natural. I suppose this has been the disappointment of my life. And I suppose that this is how we get to the middle ground. By exploring the ends and inching toward the middle.

A couple of things in Jenee Harris’ article jumped out at me:

1. “My white mother has developed an acute sensitivity to the subtle ways prejudice and bigotry pop up in daily life.”-

I wonder if my father would say he has developed the same. I think so…I think that happened when he entered into a relationship with my (black) mother and grew deeper as he witnessed my experience… but we never talk about it…

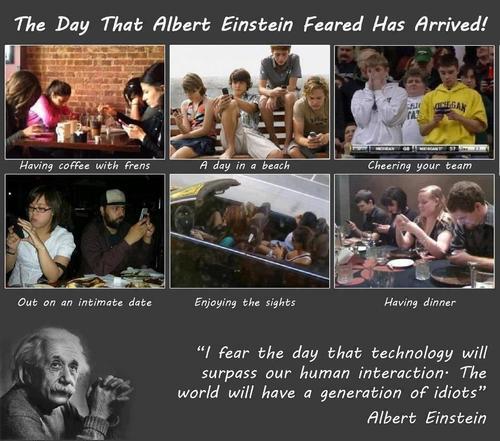

me with my parents:)

2. “Well-intended”– re: “adults loved to tell me that people paid “good money” for hair like mine (think 1980s-era perms on white women)” and “A friend got the biscuit analogy…: God burned black people and undercooked white people, but removed her from the heavenly oven at the perfect moment.”

Well…if the intention of the (white) person who said this is to make the biracial person feel better about the perceived plight of their kind…well…i guess one could count that as a good or harmless intention. But I think that summation signifies complacence. I, however, have to challenge this notion. You see, giver of said “compliment,” in your quest to make me feel better about being my invisible, displaced, misunderstood, marginalized and tragic self you put me on the receiving end of your pity, your assumptions and judgements. I do believe this is usually unconscious. I also must acknowledge that it is an assumption I’m making. Yet there’s a reason that I assume that this is the intention behind the compliments. The assumption is based on experience, but even those are dangerous to make. It’s the tone with which these comments are usually, subtly uttered. If you’ve been the biracial person in this kind of conversation, I think you know what I mean.

When I engage in this kind of innocent interaction I can be left feeling frustrated, upset, and worst of all unseen. It is depressing. It is literally a depression of my spirit. Of my freedom. A depression of my freedom to just be and simply experience this life without being saddled with the weight of the stigma of a couple hundred years of prejudice, condemnation, fear, greed, inferiority, superiority, discrimination, and antagonism. My take on it is that some people assuage a fleeting feeling of guilt over the fact that this is the biracial’s lot in life by reminding us (and/or reminding themselves) that I should be happy because I have good hair and tan skin which, I infer from your comments, should make up for the fact that on the whole the society we live in cannot acknowledge or understand how I exist. I thought there was more to that sentence, but I think that’s it. Our nation’s identity continues to be wrapped up in race and all the baggage that comes with it. For that to remain intact, biracial just can’t really be. I don’t think that needs to remain intact. I think things are shifting. So slowly. But they are shifting and I hope I stay awake enough to the shift to feel when my assumptions based on past experience are truly no longer valid.

On the other hand, I’m fairly certain that most of my response falls into the category of “Oh, come on, stop being so sensitive.”

Or am I just being truthful? That’s the stuff that this brought up for me.

Biracial Children: Racism Advice for White Parents

Race Manners: Comments about the superior beauty of your biracial child aren’t just weird — they’re troubling.

By Jenée Desmond-Harris

Updated Monday April 8, 2013

The Root —

“I’m a Caucasian woman with a biracial child (her father is black). I live in a predominantly white community. Why is it that whenever people discover that I have a ‘mixed’ child, they always say things like, ‘Oh, he/she must be so cute/gorgeous/adorable, those kids are always the best looking. You are so lucky.’

I know they mean well, but it seems off to me, and maybe racist. Do they mean compared to ‘real’ black children? When a German and Italian or an Asian and Jewish person have a child, black people don’t say, ‘Mixed children like yours are always the best looking.’ (Plus, it’s not true — not all black-white biracial kids are the ‘best looking.’)

Am I being overly sensitive by feeling there’s something off about these comments? If not, what’s the best way to respond?”

I chose this question for the first installment of Race Manners, The Root‘s new advice column on racial etiquette and ethics, because it hits close to home. Like your daughter, I’m biracial. Like you, my white mother has developed an acute sensitivity to the subtle ways prejudice and bigotry pop up in daily life. I should know. She calls me to file what I’ve deemed her “racism reports.”

And let’s be clear. Americans of all races say bizarre things to and about mixed people, who can inspire some of the most revealing remarks about our black-white baggage. Just think of the public debates about how MSNBC’s Karen Finney, and even President Obama, should be allowed to identify.

But the comments in your question often come from a good place, and they’re often said with a smile. When I was a child, adults loved to tell me that people paid “good money” for hair like mine (think 1980s-era perms on white women) and for tanning beds (again, it was the ’80s and ’90s) to achieve my skin color. Thus, the grown-up argument went, I should be happy (even if these trends didn’t stop people from petting my curls as if I were an exotic poodle, nor did they give me the straight blond hair I envied, and it’s not as if I was on the receiving end of the beauty-shop payments).

A friend got the biscuit analogy. Wait for it: God burned black people and undercooked white people, but removed her from the heavenly oven at the perfect moment, she was told.

Awkward. Well-intended. Poorly thought-through. A window into our shared cultural stuff about identity. These statements are all these things at once.

That’s another reason I selected your question. When it comes to remarks that are so obviously dead-wrong to some of us, and so clearly innocuous to others, there’s often little energy for or interest in breaking down the explanation that lies between “Ugh, so ignorant!” and “Oh, come on, stop being so sensitive.”

I’ll try it out here.

You’re right to be bothered by the remarks from the Biracial Babies Fan Club. Here’s why: These people aren’t pulling an arbitrary appreciation for almond-colored skin and curls from the ether. Instead — even if they are not aware of this — they’re both reflecting and perpetuating troubling beliefs that are bigger than their individual tastes. Specifically, while “mixed kids are the cutest” is evenhanded on its face, treating both black and white (and all other ethnic groups) as inferior to your daughter, I hear it as anti-black.

As Marcia Dawkins, the author of Clearly Invisible: Racial Passing and the Color of Cultural Identity, told me, “The myth that mixed-race offspring are somehow better than nonmixed offspring is an example of ‘hybrid vigor,’ an evolutionary theory which states that the progeny of diverse varieties within a species tend to exhibit better physical and psychological characteristics than either one or both of the parents.”

And just take a wild guess how this idea has popped up for black people. You got it: In order to demean and oppress African Americans, thought leaders throughout history, including the likes of Thomas Jefferson, have said that black-white mixed offspring are better, more attractive, smarter, etc., than “real” blacks and not as good or attractive or smart as “real” whites, Dawkins explains.

So alleging that mixed kids are the best of anything sounds different when you consider that we’ve long put a wholesale premium on all that’s whiter and brighter.

Nowhere is that premium more stubbornly applied today than when it comes to the topic at the center of your question — beauty and attractiveness. In recent memory, we had to re-litigate the harms of colorism when Zoe Saldana was cast to play the lead in a Nina Simone biopic. Tamar Braxton and India.Arie have both been accused of bleaching skin — as if that would be a reasonable thing to do.

A writer lamented in a personal essay for xoJane that she was sick and tired of being complimented for what black men viewed as her “mixed” or “exotic” (read: nonblack) physical features. (As far as I know, “you look a little black” is not a common line of praise among other groups.) Black girls still pick the white dolls in recreated Kenneth Clark experiments. Harlem moms can’t get Barbie birthday decorations in the color of their little princesses. We treated rapper Kendrick Lamar like the department store that featured a wheelchair-bound model in an ad campaign when he cast a dark-skinned woman as a music-video love interest.

Against this backdrop of painful beliefs that people of all colors buy into, yes, “Mixed kids are the cutest” should sound “off.”

As the mom of a mixed kid, you signed up for more than just the task of venturing into the “ethnic” aisle of the drugstore and learning about leave-in conditioner. You took on the work of hearing things like this through the ears of your daughter, and you agreed to have a stake in addressing racism. The fact that these comments bothered you means you’re on the job.

So if it’s at all possible, you should explain everything I’ve said above to people who announce that your daughter is gorgeous based on racial pedigree alone. If you’re shorter on time or familiarity, you could try a reminder that there’s really no such thing as genetic purity in the first place (“Great news, if that’s true, since most of us — including you — are mixed”). As an alternative, the old cocked-head, confused look, combined with “What makes you say that?” always puts the onus back on the speaker to think about what he or she is really saying.

Finally, just a simple, “Thanks, I think she’s beautiful, but I don’t like the implication that it’s because of her ethnic makeup,” could open up an important introductory conversation about why comments about superior biracial beauty aren’t true and aren’t flattering, and why the beliefs they reflect aren’t at all “cute.”

Need race-related advice? Send your questions to racemanners@theroot.com.

The Root‘s staff writer, Jenée Desmond-Harris, covers the intersection of race with news, politics and culture. She wants to talk about the complicated ways in which ethnicity, color and identity arise in your personal life — and provide perspective on the ethics and etiquette surrounding race in a changing America.

![[CONFESSIONS]<br /><br /><br /><br />

�I�m Hiding My Interracial Relationship From My Parents�](https://i0.wp.com/static.ebony.com/interracial_couple_caro2_article-small_22298.jpg)

![17mixedirish3[1].r](https://mulattodiaries.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/17mixedirish31-r.jpg?w=368&h=246)