Taking into consideration the lunch counter sit-ins of 1960, I think this is a remarkable story…

Area Woolworth’s first black sales clerk calls hiring proud moment

Jean Fisher Curry was hired in 1961 to work a cosmetics counter in the front of the store.

By Tom Stafford

SPRINGFIELD — There were no lunging police dogs with bared fangs, no fire hoses knocking people to the ground, no instigators putting cigarettes out in the hair of protesters at lunch counter sit-ins.

The first apparent outward sign that Springfield’s F.W. Woolworth store would have its first ‘‘Negro’’ employee — to use the word customary at the time — was a note Jean Fisher, 15, received in class during the fall of 1961, her junior year at South High School.

“I was never in trouble,” said Jean Fisher Curry of Springfield. So when she got the note from the counselor’s office, “I thought, what did I do?”

It wasn’t what she did that was notable but rather what she was about to do.

Like other Distributive Education students, she was told she’d have to meet the standards: keep a B average and take special classes in the department.

“I think (Distributive Education) was the forerunner of the vocational school,” Curry explained.

But if she met the standards, she could work at Woolworth’s — the downtown one at High and Limestone streets.

The importance of that was not lost on Curry: “They didn’t have black people working in the store.”

A happy clerk

“I thought I’d be cleaning,” Curry said.

That might have been OK. Her mother had done that for years in what was called “private family work” — working as a domestic at the Tanglewood Drive home of Seymour and Anne Klein.

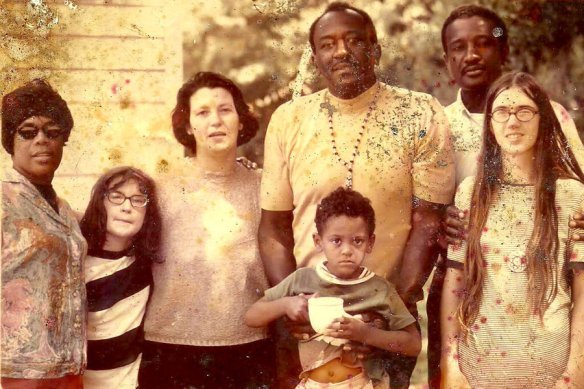

Jean Curry hugs her mother, Alberta Fisher, whose encouraging words helped her break new ground as the first black sales clerk at Springfield’s Woolworth store. Photo by Marshall Gorby.

Being a domestic “never bothered her,” Curry said, “because that was honest work.”

And when the Kleins asked Alberta Fisher to run the lunch counter at Victory Lanes, it showed “they trusted her,” Curry said. “And she was happy with that.”

The job at Woolworth’s wasn’t a cleaning job, however — likely because the Distributive Education program didn’t train people for that task.

“They told me it was a sales clerk,” said Curry,” and I said, ‘Yeah.’ ”

As it turned out, her post would be at the cosmetics counter in front of the store, where she’d be seen by all who walked in the main entrance.

The sightings began soon after she turned 16 on Sept. 15, 1961, and got her work permit.

Shades of discrimination

Curry discovered a shade of racial reasoning involved in her placement in the store.

“They hired a black girl from North and me from South,” she explained. “Because I was light (-skinned), I worked at the front of the store. Because she was darker she worked in the back of the store with the pets.”

Asked whether that was the real reason for the assignments, Curry was emphatic: “There’s no doubt. I knew it, she knew it, and she resented it.”

Curry said that colored her attitude toward her own work: “What was I going to be mad about? I didn’t feel discrimination like somebody darker.”

The attitude ran in her family.

When the census came, the light-skinned Curries listed their race as mulatto., and in the militant black pride era, they joked about being “high yellow.”

Still, they had to follow rules of the racial road.

Springfield then was a town in which blacks weren’t allowed in the Liberty Theater and in which blacks were suspicious of drinking out of segregated fountains, wondering what white people put in them.

Blacks also tended to “stay within our culture,” Curry said, taking the elevator in the Arcade to the music store that catered to their tastes and frequenting the Center Street YMCA.

Woolworth’s also had its rules: Blacks could order only carry-out from the food counter.

And when Curry started, “we were told when we gave people change to lay it on the counter,” she said, thus avoiding problems with white customers who were uncomfortable having physical contact with blacks.

“But like I told (the girl from North),” Curry added, “we may get some money.”

At first, the pay was 65 cents an hour. The following year, it would go up to 85 cents — this in an era when $1 an hour was considered decent pay, Curry said.

In her youthful enthusiasm, “I didn’t think it was a job. I thought it was a career.”

In the same spirit, Curry, who knew that the actress Betty Hutton’s sister, Barbara, was part owner of the chain, half expected one or the other Hutton sister to show up some day, coming through the front door right into her area.

When she told people she worked at Woolworth’s “I always said ‘F.W.’ like I knew him.”

“I couldn’t even tell you what F.W. stood for.”

Her mother and God

The non-Hutton whites who came into her area in the front of the store fell into a couple of categories, Curry said.

“The older ones, the little white-haired ladies, they liked me,” she said.

“They were used to black people working in their homes and knowing their place. And I knew my place.”

“The other ones, I had to grow on them,” she said.

And she did, using the enthusiasm and bedrock values her mother taught her.

Part of it was common courtesy. “I was always very friendly. You just do that,” Curry said.

Also, “we were very religious,” she said. “We went to church. I think God had a place in that.

Constantly on her mind at that time was the desire “to make my mom and dad proud of me,” Curry said.

Finally, there was the work ethic her mother sought to instill in her children.

Throughout their childhoods, Mrs. Fisher recited a saying to her children to encourage them to do the best they could in everything they did.

“She said it so much to me that I knew it by heart,” Curry said.

All that you do, do with your might. Things done by half are never done right. All that you do, do with a zeal. Those that reach the top, have to climb the hill.

Touching moments

If some of the white people of the time were uncomfortable touching blacks, the black friends and family who came to the store were the opposite.

They’d reach out, touch her and say “It’s so good to see you” when they came in, Curry recalled.

Her mother was especially proud.

“Out of all the girls, they chose her to be there,” said Mrs. Fisher, now 91, who also lives in Springfield.

“I was excited about it, really I was,” she continued. “All my whole family — my sisters, everyone — I was just telling everybody. And I still tell it now.”

Curry said the Woolworth’s experience helped her to feel a part of the larger community.

Already with a sense that Woolworth’s was a cut above the competitors of Kresge and McCrory’s, Curry soon got to know the downtown merchants as they stopped into Woolworth’s — people like William Greene, owner of an exclusive dress shop.

“I could go into stores and they’d let me lay things away. A lot of time black people couldn’t go into those stores,” she said.

Knowing as a customer, the mistress of one of the downtown businessmen also marked her as an insider.

“I felt like I was part of Springfield because I was doing those things,” Curry said.

“It wasn’t that I wanted to be white. I was being accepted for who I was, making the best of it. And I said some day I’ll tell these stories to my grandchildren, and they’ll love it.”

SOURCE

Original caption: Photo shows Mrs. Alice Rhinelander surrounded by relatives as jury decides case…Rhinelander jury locked for night; both sides anxiously await verdict. “Sentiment, passion, and prejudices should not interfere with your honest determination,” Justice Morschauser charged jury deciding Rhinelander case. Having failed to reach a verdict by 5:50 p.m. December 4th, they were ordered locked for the night. Left to right: Mrs. Jones, Alice, Grace, Jones, and Emily awaiting verdict.

Original caption: Photo shows Mrs. Alice Rhinelander surrounded by relatives as jury decides case…Rhinelander jury locked for night; both sides anxiously await verdict. “Sentiment, passion, and prejudices should not interfere with your honest determination,” Justice Morschauser charged jury deciding Rhinelander case. Having failed to reach a verdict by 5:50 p.m. December 4th, they were ordered locked for the night. Left to right: Mrs. Jones, Alice, Grace, Jones, and Emily awaiting verdict.