I think Professor Daniel hit the nail on the head with this statement from the article below: “There’s really no understanding when a person says, ‘I’m biracial, I’m multiracial,’ ” he said. “People don’t know where to locate you.” This is exactly why this work, this topic is so important to me. My sincerest hope is that one day a person can say “I’m biracial/mixed,” and that the majority of Americans will have a basic understanding of what that means to said person. Right now it’s very vague. Right now, said person is likely to get a blank stare, a condescending smirk, an accusation of self-hatred and/or denial, and then be “coded” into the category that phenotype makes most logical. Right now, the majority of people do not understand that the fact that said person comes from two different races and cultures is important to them and informs their identity. We can’t separate the two things. Hopefully wouldn’t want to.

Framing mixed race: The face of America is changing

By Jennifer Modenessi

Contra Costa Times

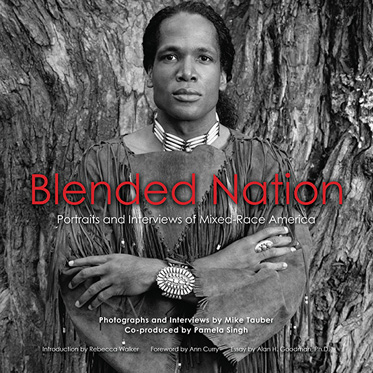

There’s no end to the number of ways people label one another, but what happens when visual cues such as skin color and hair texture don’t fit into categories? Mike Tauber and Pamela Singh interviewed and photographed more than 100 individuals and families (in the recent book “Blended Nation: Portraits of Mixed-Race America,”), capturing the faces and stories of what the authors describe as a group of people dealing with disparity, and living within the gap between how society views them and how they self-identify.

“Some people think I’m just tan and not half-black,” said 10-year-old Isabella Carr. Several years have passed since Isabella, her siblings and her parents, Janine and Evan, who are now divorced, were interviewed and photographed for “Blended Nation.”

In the book, the family talked about the rewards and challenges of their heritage. Being married to an African-American man had allowed Mozée to “see the world through a multicolored lens, and not just the white one I was born with.”

Still, there have been cloudy spots.

“I have people that don’t think they’re my kids or they ask if they have the same father,” Mozée said. She responds that, yes, they are her children and, yes, they have the same father. The conversation might be different with a stranger but Mozée “doesn’t get into those situations much.”

When asked a few years ago by the authors how he self-identified, Mozée’s eldest son, Austin, said that half the time he felt black, the other half of the time he felt white. Now 16, Austin said not much has changed.

“I identify with both ways, white and black,” he said. “I might talk to somebody and nearly make friends and that’s one of the questions they ask: ‘Are you mixed? Are you black and white?’ — partly because of how I look and my personality. I just tell them who I am. I have no problem with that.”

For some, the question never comes. Moses, 29, an Oakland resident, said she’s rarely asked about her ethnicity or background. With her pale skin, long red hair and freckles, not many people guess that her late father was black, Native American and white.

“People don’t see me as mixed” she said. “(They) don’t ask.”

Getting older, Moses said, has tempered her response to being multiracial. Living in the Bay Area, with its rich diversity, has also helped.

“On the East Coast, it was ‘No way.’ It was shock and disbelief,” Moses said. “Here, it ranges from ‘Uh-huh,’ like it’s not a real surprise, to ‘Interesting.’ It doesn’t blow people’s minds.”

Daniel, who for more than two decades has taught “Betwixt and Between,” a UC Santa Barbara course dealing with multiracial identity, has struggled with people’s perception of his mixed-race background.

“There’s really no understanding when a person says, ‘I’m biracial, I’m multiracial,’ ” he said. “People don’t know where to locate you. They know where to locate blacks. They know where to locate whites. They know where to locate Native Americans, Latinos. When you say, ‘I’m biracial, multiracial,’ they say, ‘Who are your people? What does that mean?’ Inevitably people will recode you into whatever they want you to be.”

That’s why self-identification is so important, Daniel said. It’s changing the way people talk about race and where mixed-race people fit in the fabric of American society. “If people really identified with the complexity of their million ancestors, we’d have a really different world,” he said.

Read more HERE