What a life! From the seemingly extreme “Take that eugenics!”attitude of her parents, to the prodiginous achievements of her childhood, on to the “passing” years Philippa Schuyler’s story encompasses so many fascinating facets of the “biracial” experience of old.

Philippa Schuyler

1931-1967

Classical pianist, writer

One of the most unusual and perhaps most tragic figures in American cultural history, Philippa Schuyler gained national acclaim as a child prodigy on the piano. Her picture graced the covers of weekly news magazines, and she was hailed as a young American Mozart. Schuyler’s life during adulthood, however, was a difficult one. She struggled with racial discrimination and with issues related to her mixed-race background, traveling the world in an attempt to find not only musical success but also an identity and a place in the world. She turned to writing in the early 1960s, visiting war zones as a newspaper correspondent, and she was killed in a helicopter crash in Vietnam in 1967. After her death she was mostly forgotten for several decades, but her life story was told in a 1995 biography.

Philippa Duke Schuyler was born on August 2, 1931, in New York and brought up in Harlem at the height of the area’s cultural flowering. The complexities of her life began with her background, for she had two singular parents. Her father George Schuyler was a journalist who wrote for one of the leading black newspapers of the day, the Pittsburgh Courier, and he was well acquainted with numerous writers in both black and white journalistic circles. He was not a civil rights crusader like many of his Harlem contemporaries, but rather a conservative satirist who rejected the idea of a distinctive black culture and later in life joined the ultra-right-wing John Birch Society. Philippa Schuyler’s mother, Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, was a white Southern belle from a Texas ranch who had married George Schuyler after coming to New York to escape a wealthy family of unreconstructed racists. They all refused to attend concerts Philippa Schuyler gave in Texas at the height of her fame.

Schuyler’s parents were in the grip of several novel theories and fads, some of which they devised themselves. They fed Philippa raw vegetables, brains, and liver, believing that cooking leached vital nutrients out of food. And, in contrast to the now-discredited but at the time widely held belief in eugenics, which formed the basis for Nazi ideas of racial purity, they claimed that racial mixing could produce a superior “hybrid” sort of human. That notion had strong effects on Philippa Schuyler’s life, for the Schuylers planned to make their daughter into Exhibit A for the gains that could be realized from black-white intermarriage.

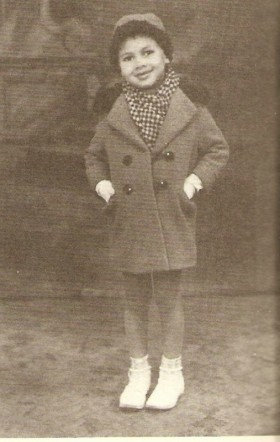

And, indeed, the plan seemed to work. Schuyler walked before she was a year old, was said to be reading the Rubaiyat poems of Omar Khayyam at two and a half, and playing the piano and writing stories at three. When she was five, Schuyler underwent an IQ test at Columbia University; it yielded the genius-level figure of 185. She made rapid progress on the piano, and due to Mr. Schuyler’s connections it wasn’t long before stories about Philippa began to appear in New York newspapers.

Schuyler’s mother, described by the New York Times as “the stage mother from hell, blending a frustrated artist’s ambition with an activist’s self-righteousness,” started to enter her in musical competitions. Schuyler did spectacularly well and was a regular concert attraction by the time she was eight. Just short of her ninth birthday, New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia named a day after her at the New York World’s Fair. But her childhood was an isolated one; she was taught mostly by private tutors and had no friends her own age. Her mother, who fired her piano teachers whenever she began to get close to one emotionally, beat her regularly.

For a period of time during World War II, Schuyler was a national child star. She wrote a symphony at age 13, and leading composer and critic Virgil Thomson pronounced it the equal of works that Mozart had written at that age after the New York Philharmonic performed it in 1945. A concert Schuyler performed with the Philharmonic soon after that was attended by a crowd of 12,000, and profiles of the attractive teen appeared in Time, Look, and The New Yorker. Schuyler was promoted by the black press in general, not just in her father’s Pittsburgh Courier, as a role model, and she certainly inspired a generation of black parents to sign their kids up for piano lessons.

But there were pitfalls ahead for the talented youngster. When she was 13, she discovered a scrapbook her mother had kept of her accomplishments, and more and more she began to feel like an exotic flower on display. On tour, especially in the South, she began to experience racial prejudice, something of which she had been mostly unaware during her sheltered upbringing. Bookings began to dry up, except in black-organized concert series. Observers have offered various explanations as to why. Schuyler herself and many others pointed to discrimination; the world of classical music has never been a nurturing one for African-American performers, and in the 1940s very few blacks indeed had access to major concert stages. Some felt that Schuyler’s playing, although technically flawless, suffered from an emotionless quality brought on by the strictures of her demanding life. And Schuyler faced a problem she had in common with other teenage sensations—the tendency of the spotlight to seek out the next young phenomenon.

Though Schuyler briefly fascinated the nation as a mulatto child prodigy, white America lost interest in her as she aged.

Schuyler and her mother reacted by once again calling in George Schuyler’s connections; he had friends in Latin American countries, and Schuyler began to give concerts there. In 1952 she visited Europe for the first time. Schuyler enjoyed travel, and, like other black performers, found a measure of unprejudiced acceptance among European audiences. Over the next 15 years she would appear in 80 countries and would master four new languages, becoming proficient enough in French, Portuguese, and Italian that she could write for periodicals published in those languages. She traveled to Africa as well as Europe, performing for independence leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and Haile Selassie in Ethiopia—but also passing for white in apartheid-era South Africa. Schuyler began to resist the pressure that still came from her parents, but she remained close to them, writing to her mother almost daily and becoming their chief means of financial support.

Her income came not only from music but also from lectures she gave to groups such as the virulently anti-internationalist John Birch Society, for Schuyler had come to share her father’s conservative politics. Despite her performances in newly independent African capitals, she came to adopt a positive outlook on European colonialism.

Confused and fearful about the future, Schuyler took steps in two new directions. First, since her ethnic identity seemed uncertain to those who had never encountered her, she began in 1962 to bill herself as Felipa Monterro or Felipa Monterro y Schuyler. She even obtained a new passport in that name. Her motivation seems to have been split between a desire to have audiences judge her without knowing of her African-American background, and a broader renunciation of her black identity. The ruse convinced audiences for a time, but the reviews of her concerts were mixed, and she soon abandoned the effort.

Second, Schuyler began to write. Traveling the globe, she filed stories from political hot spots for United Press International and later for the ultraconservative Manchester Union Leader newspaper in New Hampshire. She wrote several books and magazine articles as well, and at her death she left several unpublished novels in various stages of completion. One of them evolved into an autobiography, Adventures in Black and White, which was published in 1960.

She traveled to Vietnam to do lay missionary work, supporting U.S. military action there and writing a posthumously published book about American soldiers, Good Men Die. She founded an organization devoted to the aid of children fathered by U.S. servicemen, and on several occasions she assisted Catholic organizations in evacuating children and convent residents from areas of what was then the nation of South Vietnam as pro-North Vietnamese guerrillas advanced. It was on one of those evacuation missions, on May 9, 1967, that Schuyler’s helicopter crashed into Da Nang Bay. She drowned, for she was unable to swim. Shortly before her death, she had written a letter that seemed to suggest a political change of heart, expressing sympathy with black activist leader Stokely Carmichael.

Schuyler’s funeral was held at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and in death she was once again in the headlines. Two years after her death, Schuyler’s mother hanged herself in her Harlem apartment. A New York City school was named after Schuyler, but her name dropped into temporary obscurity. She became better known with the publication in 1995 of Composition in Black and White: The Life of Philippa Schuyler, a biography by Kathryn Talalay. In 2004, star vocalist Alicia Keys was signed to portray Schuyler in a film co-produced by actress Halle Berry. “This story is so much about finding your place in the world,” Keys told Japan’s Daily Yomiuri newspaper. “Where do we really fit in, in a world so full of boxes and categories?”