I enjoyed and appreciated this article about “us.” I’ve been thinking lately about the choice we have to either “interact with the system the way it interacts with you,” or to come up with (and stick to and be ready to defend) our own definition of self. In other words, you can let everyone else define you because it’s the path of least outward resistance, or you can follow the path of the least inward resistance. I tried to go along with the system. I think that was the primary source of my former discontent. Now that I’m being true to myself, lots of things make a lot more sense and the possibilities seem greater. Other things seem to make no sense at all and the obstacles loom large. Yet I’m confident that I’m heading in the right direction.

For fast-growing group of Americans, race isn’t defined by one name

The question hit Tiffanie Grier like a hammer, and more than 15 years later, the impact lingers. She was just 9 years old, a third-grader at a school awards program, when she was asked by a friend’s mother about her ambiguous racial appearance.

What are you?

For Grier, now 26 and career placement director for the Boys & Girls Club of Greater Memphis, it was the first of many instances in which she confronted questions related to her heritage as the daughter of a white mother and an African-American father.

“I get asked a lot,” she said. “(People) feel the need to know.”

Far from being a rarity, however, Grier is part of what may be the fastest-growing demographic, both locally and nationally.

Between 2000 and 2008, the number of people of two or more races rose nearly 33 percent, from 3.9 million to nearly 5.2 million nationwide, according to census estimates.

In Shelby County, the growth rate was even faster. The number of multiracial residents increased some 43 percent, from 6,384 to 9,113 during the eight-year period in which the overall county population grew by only about 1 percent.

The 2010 Census, barely two months away, is expected to show even greater growth in the category, demographers say.

The reasons are twofold. First, the number of interracial marriages, and the children produced by them, has risen steadily since 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down state prohibitions on the unions.

Second, as a result of a growing acceptance of multiracial heritage, researchers say, people have become increasingly willing to check more than one category for race on the census forms. The election of a mixed-race president, Barack Obama, likely will reinforce that trend.

“It’s the wave of the future, for sure,” said William Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution in Washington. “I think symbolically … it might have an impact on how people view race.”

The upcoming census will be only the second in which respondents are able to identify themselves as multiracial.

The 2000 Census showed the emerging “two-or-more-races” group was poised for rapid growth. About 42 percent of them were under age 18, compared to only 25 percent of the general population that young, and 70 percent were younger than 35.

“What that’s telling you is that it’s a young population, and that it’s increasing,” said Nicholas Jones, chief of the Census Bureau’s racial statistics branch.

Among the most common combinations named by people in the two-or-more-races category in 2000 were white-Native American/ Alaskan (1.08 million), white-Asian (about 868,000) and white-black (nearly 785,000).

The significance of the emerging multirace demographic is anything but clear. Frey predicts it will diminish the importance of race — helping to propel society beyond a black-white divide — while others say the impact will be more on a personal level.

“I think it’s important to the people themselves — how they identify themselves,” said Darryl Tukufu, vice president for academic affairs and associate professor of sociology at Crichton College in Memphis.

(PHOTO BY MIKE BROWN: Memphians (clockwise from top left) Felicia Scarpeti-Lomax, Tiffanie Grier, Cardell Orrin and Desireé Robertson are members of what may be the fastest-growing demographic, both locally and nationally — people who may identify themselves by two or more races.)

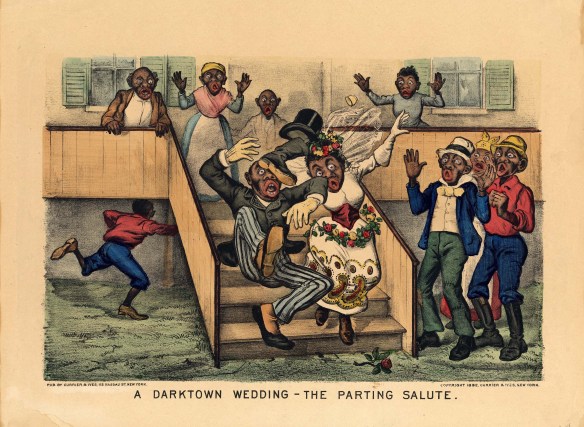

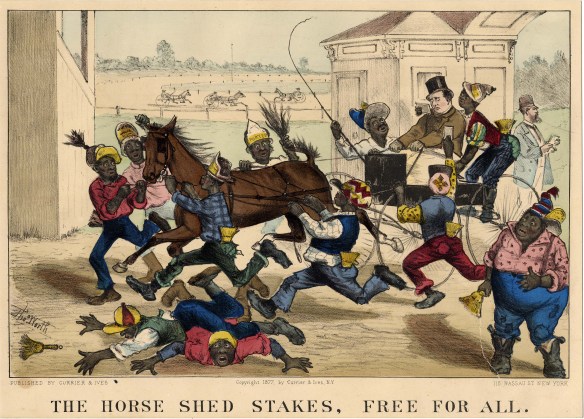

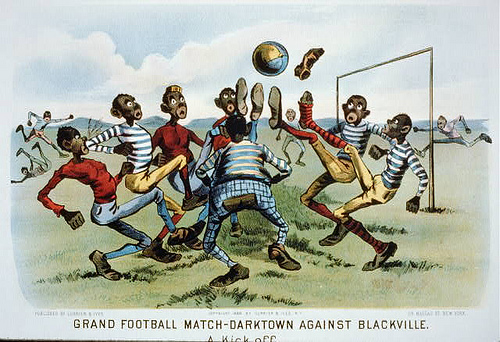

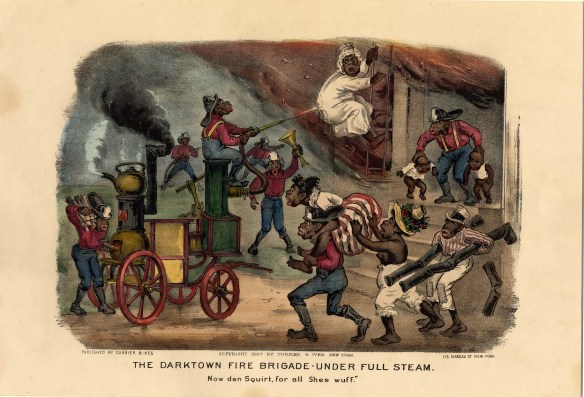

Whatever other effects it might have, the relatively recent census acceptance of multiracial classification recalls the nation’s troubled and convoluted history regarding race.

Although many African-Americans have some white ancestry, the historic “one-drop rule” meant that anyone with so much as a drop of black blood was categorized as black and potentially subjected to disenfranchisement and other forms of discrimination.

That history, said Warner Dickerson, president of the Memphis Branch of the NAACP, blurs the significance of the new census categories.

“I happen to be a fair-skinned black man, and you and I both know why,” Dickerson said. “Most of us are mixed with black blood and white blood.”

Because society has labeled them as black, many people with one African-American and one white parent say they will continue to check only the black category on the census form.

“I will be addressed, especially here in the South, as an African-American,” said Cardell Orrin, 35, a Memphis business consultant and co-founder of a political action committee called New Path. “You decide to make your own definition or interact with the system the way it interacts with you.”

Tukufu said the labeling, and discrimination that accompanied it, tended to instill in many mixed-race people a pride in their black heritage. That’s why they’ve stuck with one racial category on census forms.

“But now you have more of the younger folks who identify with both,” he added.

Grier interviewed people of ambiguous racial appearance, including many of mixed heritage, for her master’s thesis at the University of Memphis. She found that the question of how mixed-race people identified themselves often depends on who raised them.

That was the case with Desireé Robertson, 37, of Millington, who was adopted by an African-American couple and didn’t discover until age 30 that her biological mother was white.

“That’s my primary identification,” Robertson said in explaining why she’ll stay with just African-American as her identity in the census.

But Felicia Scarpeti-Lomax, 39, who was raised by both her white Italian-American mother and her black father, plans to use both racial categories.

“For me to use one racial category, that would be eliminating one of my parents, and that’s not my heritage,” Scarpeti-Lomax said.

She formerly lived in New York City, where racial identity was never an issue, she said.

“I never faced this craziness until I moved to the South,” she said.

Scarpeti-Lomax, like many others of biracial heritage, said she’s glad the Census Bureau finally began offered the choice of multiple categories.

“This is 2010 …” she said, “and I just refuse to live my life identified by a color.”

Fifty years after he first started doing work for the magazine, Norman Rockwell was tired of doing the same sweet views of America for the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1960s. The great illustrator was increasingly influenced by his close friends and loved ones to look at some of the problems that was afflicting American society. Rockwell had formed close friendships with Erik Erickson and Robert Coles, psychiatrists specializing in the treatment of children and both were advocates of the civil rights movement.

Fifty years after he first started doing work for the magazine, Norman Rockwell was tired of doing the same sweet views of America for the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1960s. The great illustrator was increasingly influenced by his close friends and loved ones to look at some of the problems that was afflicting American society. Rockwell had formed close friendships with Erik Erickson and Robert Coles, psychiatrists specializing in the treatment of children and both were advocates of the civil rights movement.

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully. It depicts the deaths of 3 Civil Rights workers who were killed for their efforts to register African American voters. It is done in a monochrome sienna color, and it is a horrifying vision of racism. A look of it can be seen

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully. It depicts the deaths of 3 Civil Rights workers who were killed for their efforts to register African American voters. It is done in a monochrome sienna color, and it is a horrifying vision of racism. A look of it can be seen