Perhaps even more influential than John Powell was Walter Plecker. Plecker dedicated his life to making sure that people like me could not exist. And though the notion predated him, I believe that he further ingrained into the consciousness of the nation the myth of the “tragic mulatto.” But even worse than that, he stripped the Native Americans of Virginia of their rights and identity. In my opinion Powell, Plecker, and the Eugenics movement in general are major pieces of this race in America puzzle.

John Powell, the renowned Richmond-born composer and pianist, clutches an American flag in this news service photograph from 1920. Wealthy Virginians and powerful newspaper editors supported the white-supremacist sentiments espoused by Powell. Fear of racial mixing was particularly pronounced among genealogy-obsessed Virginians who wanted to maintain a “pure” bloodline.

Disdaining the Ku Klux Klan’s violent white supremacist policies and tactics, elite white Virginians embraced the scientific racism espoused by the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America. Founded in Richmond in September 1922 by internationally renowned pianist John Powell, self-styled ethnologist Earnest Sevier Cox, and Walter Plecker, the ASCOA committed itself to preserving white “racial purity.” Powell provided the movement’s star power and publicity; Cox’s book White America (1923) provided the pseudoscientific, eugenic justifications; and Plecker backed the other two with the state’s police power. The ASCOA demanded legislation prohibiting interracial marriage and defining anyone with any non-white heritage—even one drop—as black.

Passed at the height of the eugenics movement, the Racial Integrity Act proclaimed the existence of only two racial categories in Virginia—”colored” and white. The law stripped Native Americans, and members of other groups with dark skin, of their land, voting rights, and legal identity.

Walter Ashby Plecker was the first registrar of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics, which records births, marriages and deaths. He accepted the job in 1912. For the next 34 years, he led the effort to purify the white race in Virginia by forcing Indians and other nonwhites to classify themselves as blacks. It amounted to bureaucratic genocide.

He worked with a vengeance.

Plecker was a white supremacist and a zealous advocate of—a now discredited movement to preserve the integrity of white blood by preventing interracial breeding. “Unless this can be done,” he once wrote, “we have little to hope for, but may expect in the future decline or complete destruction of our civilization.”

Plecker would recall his early days in a letter to a magazine editor expressing his abhorrence of interracial breeding. He remembered “being largely under the control” of a “faithful” slave named Delia. When the war ended, she stayed on as a servant. The Pleckers were so fond of her that they let her get married in their house. When Plecker’s mother died in 1915, it was Delia “who closed her eyes,” he wrote.

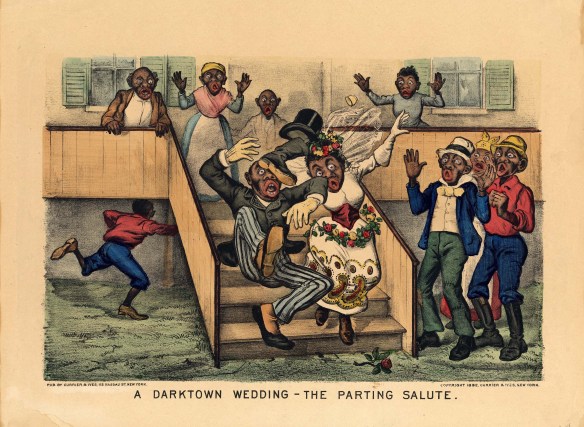

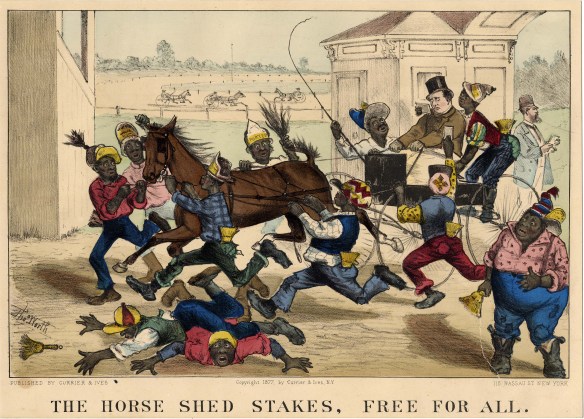

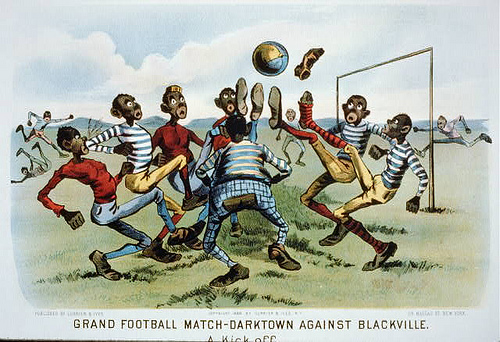

Then Plecker got to his point. “As much as we held in esteem individual negroes this esteem was not of a character that would tolerate marriage with them, though as we know now to our sorrow much illegitimate mixture has occurred.” Plecker added, “If you desire to do the correct thing for the negro race … inspire (them) with the thought that the birth of mulatto children is a standing disgrace.”

Walter Plecker sits at his desk in 1935 at the Bureau of Vital Statistics

Plecker was a devout Presbyterian. He helped establish churches around the state and supported fundamentalist missionaries. Plecker belonged to a conservative Southern branch of the church that believed the Bible was infallible and condoned segregation. Members of Plecker’s branch maintained that God flooded the earth and destroyed Sodom to express his anger at racial interbreeding.

“Let us turn a deaf ear to those who would interpret Christian brotherhood as racial equality,” Plecker wrote in a 1925 essay.

Plecker saw everything in black and white. There were no other races. There was no such thing as a Virginia Indian. The tribes, he said, had become a “mongrel” mixture of black and American Indian blood.

Their existence greatly disturbed Plecker. He was convinced that mulatto offspring would slowly seep into the white race. “Like rats when you’re not watching,” they “have been sneaking in their birth certificates through their own midwives, giving either Indian or white racial classification,” Plecker wrote.

Many who came into Plecker’s cross hairs were acting with pure intentions. They registered as white or Indian because that’s how their parents identified themselves. Plecker seemed to delight in informing them they were “colored,” citing genealogical records dating back to the early 1800s that he said his office possessed. His tone was cold and final.

In one letter, Plecker informed a Pennsylvania woman that the Virginia man about to become her son-in-law had black blood. “You have to set the thing straight now and we hope your daughter can see the seriousness of the whole matter and dismiss this young man without any more ado,” he wrote.

In another missive, he rejected a Lynchburg woman’s claim that her newborn was white. The father, he told her in a letter, had traces of “negro” blood.

“This is to inform you that this is a mulatto child and you cannot pass it off as white,” he wrote.

“You will have to do something about this matter and see that this child is not allowed to mix with white children. It cannot go to white schools and can never marry a white person in Virginia.

“It is a horrible thing.”

Plecker demanded the removal of bodies from white cemeteries. He tried to evict a set of twins from a Presbyterian orphanage because they were illegitimate and, therefore, the “chances are 10-1 they are of negro blood.”

Plecker maintained that all of his racial designations were based on impeccable records. There was, however, a secret Plecker revealed to only a few trusted allies: A lot of the time he was just guessing.

He acknowledged the sham when a Richmond attorney questioned his authority to change the birth certificate of a woman classified as an Indian before 1924. Plecker quietly admitted he had no such power and rescinded his designation of the woman as “colored.”

Plecker fretted that he would lose his hold on Indians if word of his retreat got out. “In reality I have been doing a good deal of bluffing, knowing all the while that it could never be legally sustained,” he wrote to his cohort, John Powell. “This is the first time that my hand has been absolutely called.”

The setback was temporary, however. The attorney kept quiet.

Plecker’s racial records were largely ignored after 1959, when his handpicked successor retired. Virginia schools were fully integrated in 1963 and, four years later, the state’s ban on interracial marriage was ruled unconstitutional. In 1975, the General Assembly repealed the rest of the Racial Integrity Act.

Virginia has tried to erase Plecker’s legacy. It has established councils on Indian affairs and has conferred official state recognition on eight tribes, a designation that provides no privileges. But Indian leaders say recognition equals respect.

The approach to healing for mixed-race Indians must be holistic, inclusive of their bi-racial and tri-racial and Indian identity.

Fifty years after he first started doing work for the magazine, Norman Rockwell was tired of doing the same sweet views of America for the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1960s. The great illustrator was increasingly influenced by his close friends and loved ones to look at some of the problems that was afflicting American society. Rockwell had formed close friendships with Erik Erickson and Robert Coles, psychiatrists specializing in the treatment of children and both were advocates of the civil rights movement.

Fifty years after he first started doing work for the magazine, Norman Rockwell was tired of doing the same sweet views of America for the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1960s. The great illustrator was increasingly influenced by his close friends and loved ones to look at some of the problems that was afflicting American society. Rockwell had formed close friendships with Erik Erickson and Robert Coles, psychiatrists specializing in the treatment of children and both were advocates of the civil rights movement.

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully. It depicts the deaths of 3 Civil Rights workers who were killed for their efforts to register African American voters. It is done in a monochrome sienna color, and it is a horrifying vision of racism. A look of it can be seen

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully. It depicts the deaths of 3 Civil Rights workers who were killed for their efforts to register African American voters. It is done in a monochrome sienna color, and it is a horrifying vision of racism. A look of it can be seen