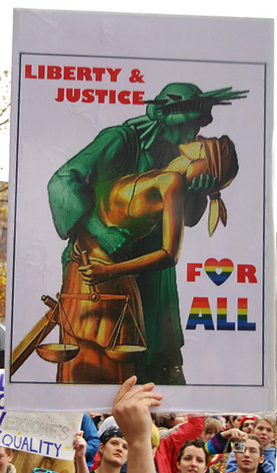

So here’s what came from my search for more on Isabella Fowler. In these paragraphs excerpted from Black Slaveowners: free Black slave masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860 by Larry Koger we see where the intraracial divide between mulattoes and “negroes”started. I must admit that I am disappointed (to say the least) in the behavior of these privileged “biracials.” I cannot defend the behavior. Don’t want to. On the other hand, it’s easy for me to sit in judgement in the year 2010 when my freedom and my opportunity for advancement are not on the line. I would love to believe that back then, were I given the choice I would free my people. That I would not see myself as separate from or better than, and that the only privilege I would take advantage of would be the one by which I could exercise my right to right some wrongs and provide an opportunity for others to be liberated and elevated alongside me. I would love to believe that… but circumstances were different and I can’t possibly know how I would have behaved. I do know that none of those attitudes/ideals have taken root in me, yet the accusations continue to be hurled and conclusions jumped to. All of that being said, it’s 2010 and the time for ridding ourselves of these old paradigms of house slaves vs. field hands is long overdue. Maybe by 2012… according to Willie Lynch (perhaps a mythical “legend”) that’s when the stronghold of slave conditioning will lose it’s grip.

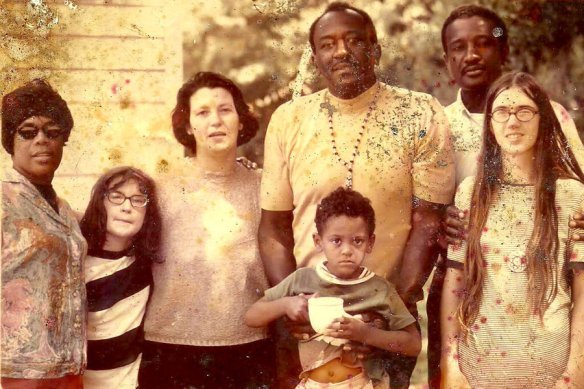

The mulatto children of slave masters, who were accepted as legitimate heirs, held a position in the household of their fathers which placed them in a superior status over the other slaves. These children were accustomed to the master-slave relationship; however, they conceived of themselves not as slaves but slave masters. In spite of the fact that they were of African descent, the white blood that ran through their veins separated them from their fellow black slaves on the estates of their fathers. For example, the children of Michael Fowler, a white planter of Christ Church Parish, and his black companion named Sibb were raised in an environment which condoned slavery. According to Calvin D. Wilson, in 1912, “there was a rich planter in Charleston named Fowler who took a woman of African descent and established her in his home…. There was a daughter born, who was called Isabella; the planter insisted that she should be known as Miss Fowler.” Clearly Michael Fowler expected his slaves to serve and regard his mulatto children as thought they were white. So the offspring of Fowler were treated as little masters and mistresses by the slaves of their father.

In fact, the process of cultural assimilation was so complete that the children of Michael Fowler, once reaching maturity and inheriting their father’s plantation and slaves, chose to align themselves with the values of white slaveowners rather than embracing the spirit of freedom and liberty espoused by the abolitionists. In 1810, the estate of the deceased Michael Fowler was divided among his mulatto children…. When the descendants of Michael Fowler received their slaves, manumission was still the privilege of the slaveowners; however, none of the heirs chose to emancipate their slaves… Undoubtedly, the children of Michael Fowler considered slavery a viable labor system and chose to hold their slaves in bondage.

Mulatto children were not always acknowledged as the offspring of white slaveholders. However, upon the death of their owners, they occasionally were manumitted and provided for once freed. These children probably were unaware of the bond of kinship to their owners. Yet that bond allowed them to receive preferential treatment from their slave masters. The unknowing mulatto offspring of white slaveowners often were trained as house servants or artisans. Although they were not acknowledged as the children of slave masters, their encounter with the culture of their masters influenced them to become slaveowners.

In fact, the slaves of both mixed and unmixed racial heritage who served as house servants or artisans accepted certain aspects of the culture of white slaveowners. Regrettably, the close interaction with the Southern culture influenced many slaves to identify with their owners. For the house slaves, the contact with their masters and mistresses perpetuated the difference between themselves and the majority of the slaves who tilled the soil. The house servants were taught to consider themselves superior to the common field hands. Furthermore, the house slaves’ conception of superiority was reinforced by their dress, food, and housing, which was slightly better than that given to the field hands. So it was that they separated themselves from the field slaves and occasionally accepted the values of their slaveowners and looked upon slavery as a justified institution. As a consequence, they envied the life of splendor that their owners enjoyed and viewed slavery as a means of obtaining the luxuries possessed by their masters.