This is a great article chronicling the changing landscape of transracial adoption. Best advice I’ve read on the matter: “those adopting must be educated to understand ‘the impact of race and racism on the country, their family and the child in particular.'”

Transracial adoptions: A ‘feel good’ act or no ‘big deal’?

By Jessica Ravitz

VIA

(CNN) — “White people adopt black kids to make themselves feel good… A black child needs black parents to raise it.” “Maybe she adopted one because the blacks in the community wouldn’t step forward and adopt?” “What’s the big deal? If no white person ever adopted a black child, they’d be saying why don’t white people adopt black children.” “Who cares what race they are? A woman got a child, a child got a mother…it’s BEAUTIFUL!!! And yes I am black…if it matters.”

These impassioned comments and thousands more poured in earlier this week when CNN published a story on the stirred-up debate surrounding Sandra Bullock’s recent adoption. A People magazine cover photo of the actress beaming at her newly adopted black infant son, and the discussions that have followed, clearly hit a nerve.

So when it comes to transracial adoptions in this country, where are we?

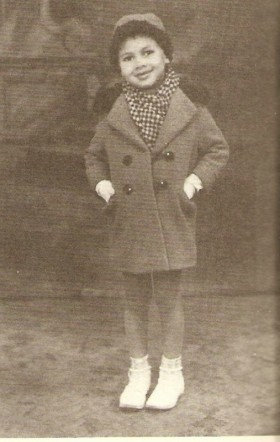

Stacey Bush is the white child of a black mother whose adoption sparked controversy and whose attitude forces people to think about the issue differently.

Stacey wouldn’t change a thing about her life, which is saying a lot for a young woman who spent her early childhood being neglected and bounced through the foster-care system. That was before a drawn-out legal case ended in 1998, allowing a single black woman, Regina Bush — the only mother Stacey had ever loved — to become her forever mom.

Regina Bush stands with her daughter, Stacey, whom she adopted after lengthy legal wrangling.

The Michigan lawsuit was filed when a county agency cited concerns about “cultural issues” in an attempt to keep the pair apart. Regina Bush’s adoption of Stacey’s biracial half-sister had already been completed, without challenge, and Bush says she wanted to keep the girls together. (As a matter of full disclosure, this CNN writer’s late father represented Regina Bush in the case.)

At 21, Stacey is thriving in college, well on her way to becoming an early-childhood educator and seamlessly moving between worlds. In one day, she might braid the hair of black friends, address faculty at Central Michigan University where she is on a partial multicultural scholarship, and then go salsa dancing with her Latina sorority sisters.

“People are sometimes startled. ‘She’s white, but she doesn’t seem white,'” she says with a laugh. “I can relate to everyone. I like being exposed to everything. … Seeing me, hearing me — it doesn’t matter what color you’re raised just as long as someone loves you.”

Forty percent of children adopted domestically and internationally by Americans are a different race or culture from their adoptive parents, according to a 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents, the most recent study of its kind conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Legislation passed by Congress in 1994 and 1996 prohibits agencies getting federal help from discriminating against would-be parents based on race or national origin.

How adoptive parents have approached transracial adoptions has changed with time, says Chuck Johnson, acting chief executive of the National Council for Adoption.

“In the old days, meaning the ’70s and ’80s, there was this notion that these parents need to be colorblind. This sounds wonderful, but by being colorblind you’re denying they’re of a different race and culture,” Johnson says. “Families that are successful are those that acknowledge race. … It’s not a curse. It’s not an impossible feat. They just need to work harder to give a child a sense of self-identity.”

It may be ideal and less complicated to match children available for adoption with same-race, same-culture families, says Johnson, who advocates that children be raised in their own countries whenever possible, too.

“But timeliness is of the utmost importance,” he says. “It’s better to find permanency and a loving home.”

The latest figures show that there are 463,000 American kids in the foster-care system, of which 123,000 are available for adoption, Johnson says. Of those, he says, 30 percent are black, 39 percent are white, 21 percent are Hispanic and the rest are of other origins.

Seventy-three percent of official adoptions — including those arranged through foster care, private domestic arrangements and internationally — are done by whites, according to the 2007 survey of adoptive parents. But that doesn’t account for informal arrangements, when relatives take in other family members’ children, which is much more common in the black community, says Toni Oliver, vice-president elect of the National Association of Black Social Workers. She says the black community takes in “more children than the whole foster care system does,” although Johnson adds that often these arrangements don’t have the safeguards and protections legal adoptions provide.

When handled well, transracial adoption is “a very positive thing,” says Rita Simon, who has been studying these adoptions for 30 years and has written 65 books, including “Adoption, Race & Identity: From Infancy to Young Adulthood.”

“But love is not enough,” said Simon, a professor of justice and public policy at American University in Washington. “You really have to make some changes in your life if you adopt a child of another race.”

In the case of a white parent adopting a black child, that might mean living in an integrated neighborhood, having pictures in the home of black heroes, seeking out other families in similar situations, attending a black church and finding role models or godparents who are black. The same need to integrate a child’s culture applies across the board, whether parents are adopting from Asia, Central America or elsewhere.

“It helps make our society more integrated,” said Simon, who has five biracial grandchildren. “Race becomes less important and other kinds of identity issues become more important.”

Bill Barry and his wife, Joan Jacobson, adopted two boys as newborns. Willie, 17, is biracial and Alex, 15, is black. Race never mattered to the white couple when they set out to adopt, after it became clear they wouldn’t be able to bear children on their own.

Bill Barry and Joan Jacobson pose with their two sons, Willie, left, and Alex, whom they adopted as newborns.

“We simply wanted a healthy newborn,” Barry says. “We didn’t care about race, didn’t care about sex, and we knew we wanted them locally.”

Had the family uprooted to white suburbia, he suspects, the journey might have been more challenging. As it is, the kids go to public schools in Baltimore, Maryland, live in a multiracial and multicultural environment and grew up in a house where pictures of Paul Robeson and Rosa Parks hung on the walls. But Barry says he and his wife didn’t “go way overboard.” The white pair didn’t, for example, suddenly start celebrating Kwanzaa.

“My wife is Jewish, though not so practicing, and we did Christmas and Hanukkah. Double the presents — they quickly celebrated that,” he says. “Kids are always trying to figure out their identity and who they are, and race is just part of it.”

That may be true, but the National Association of Black Social Workers has long argued for keeping black children in black homes. About 40 years ago, the association released a four-page position paper on transracial adoption in which it went so far as to call such adoptions “genocide” — and that word choice has dogged the organization ever since.

But Oliver, the vice-president-elect, says when that position was written decades ago, blacks were being discounted as adoptive parents, not being given the same resources to help keep families together and thereby prevent the need for child placements, and that agencies weren’t recruiting families within the community. By speaking strongly, the organization helped jolt the system — although more still needs to be done, she says.

The preference, Oliver says, remains that kids be placed in same-race households whenever possible. And if it isn’t possible, or if a birth parent selects an adoptive family of a different race, then those adopting must be educated to understand “the impact of race and racism on the country, their family and the child in particular,” she says.

“There is a negative impact that children and families are going to experience based on race,” she says. “The idea that race doesn’t matter is not true. We would like it to be true, but it’s not.”

Regina and Stacey Bush have faced challenges along the way. They’ve received their share of stares and under-the-breath comments like, “What’s this world coming to.” When a young Stacey once started climbing into the van to join her family at an Arby’s restaurant, patrons came running to grab her, yelling that she was going into the wrong car. The girl was given detention at school, accused of lying because she called a young black boy her little brother, which he was. At a movie theater one time, someone called the police because they feared Stacey had been abducted.

Regina says she got attacks from both sides.

“White babies were a precious commodity. ‘Blacks can’t take care of white children,'” she remembers hearing. “And blacks were outraged” because there are so many black children in the system who need homes, and “they didn’t understand why a black woman wouldn’t adopt one of her own.”

But she says she simply wanted to keep Stacey and her half-sister in the same home and give them a loving family, together.

Stacey says that upbringing taught her to embrace all people.

“It gave me so much opportunity to talk to so many different people. There were no limitations. I stood up for a lot of things, and it made me break peoples’ mind-sets,” she says. “We’re accountable for each other as brothers and sisters. We need to look out for each other because at the end of the day we’re all human beings.”