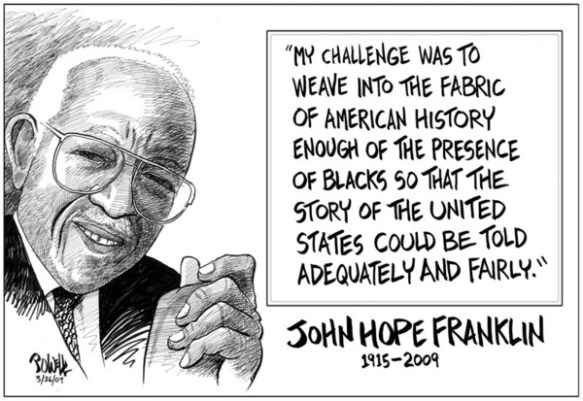

This entire post is reblogged from Renegade South: histories of unconventional southerners. I find it to be a fascinating piece of American history. It’s one of those stories in which “american” history and “african-american” history are so intertwined that a distinction between the two can hardly be made. That’s just how it always should be, in my opinion. This country has just one history. It’s black and white and everything in between. The story is long and may be hard to follow, but I think it’s worth the effort.

The Family Origins of Vernon Dahmer, Civil Rights Activist

Vernon F. Dahmer, a well known Mississippi civil rights worker, was murdered in 1966 by white supremacists connected to the Ku Klux Klan. Before the night of January 10, 1966, when the Dahmer grocery store and home were firebombed, Vernon had been leading voter registration drives in his community. To facilitate that effort, he had recently placed a voter registration book in the grocery store he owned.

Vernon Dahmer’s grocery store, located on Monroe Road, 3.5 miles from the Jones County line. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

It took many years and five court trials to convict KKK Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers in 1998 of having ordered the murder of Vernon Dahmer. Today, Dahmer is revered for his courageous work on behalf of black civil rights. In honor of his memory, both a street and memorial park in Hattiesburg bear his name.

In the essay that follows, Dahmer’s grandniece, Wilmer Watts Backstrom, and Yvonne Bivins, a member of his extended family, enrich our understanding by telling the story of his family roots in southern Mississippi. Dahmer’s multiracial heritage included white, black, and Indian ancestors. The narrative begins with the story of his grandmother, Laura Barnes.

The Family Origins of Vernon F. Dahmer, Mississippi Civil Rights Activist

By Wilmer Watts Backstrom and Yvonne Bivins

Laura Barnes was born in Jones County, MS in October 1854. According to her daughter, Roxanne Craft, “she was given to a black family to raise because she was born out of wedlock to a white girl.”

The 1870 census for Twp 9 in NE Jones County, Mississippi, shows that fifteen-year-old Laura was living in the household of Ann Barnes, a 55-year-old mulatto woman born in Mississippi whose occupation was housekeeper. A young mulatto boy, Augustus, age 12, also lived in the home. Living next door to the Barnes family were Andrew and Annice (Brumfield) Dahmer.

Laura Barnes, grandmother of Vernon Dahmer, Sr., courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

After the Civil War, Andrew Dahmer and his brothers became traveling salesmen who peddled their wares in Wayne, Jones, and Perry Counties in Mississippi. Andrew soon met and married Annice Brumfield, whose mother, Altamarah Knight Brumfield, was the daughter aunt of Newt Knight and Serena Knight.

Andrew and Annice’s neighbor, Laura Barnes, met Andrew’s brother, Peter Dahmer, in the early 1870s. They began a relationship that resulted in the birth of a baby boy in 1872, who Laura named George Washington Dahmer. Peter apparently did not acknowledge his child, and soon moved to Chickasaw County with several brothers, where they farmed and built a mercantile business.

For giving birth out of wedlock, Laura became a “marked woman.” During this period in her life, she operated a boarding house for the railroad and sawmill workers in northeast Covington County and near “Sullivan’s Hollow” in Smith County. The “Hollow” was notorious for its lawlessness and racial bigotry. Blacks were not welcome there. Black families that did live there were descendants of Craft and Sullivan slaves.

Laura hired a black man from the hollow named Charlie Craft. Working closely together on her place, they soon fell in love and developed a relationship. This would bring trouble, because although Laura was raised by a mulatto woman and listed as mulatto on census records, whites still considered her off limits to a black man.

Charlie and Laura Barnes Craft, grandparents of Vernon Dahmer. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

Charlie Craft was born in Smith County, MS, around 1853. According to family history, he was part Creek Indian and part African, with piercing eyes and coal black straight hair. A former slave of Bryant Craft, Charlie was known as a man who had never run from a fight. Story has it that after a shootout with the infamous Sullivans, he left Smith County, but doubled back to spirit away his siblings. Because newly freed slaves were not welcome in Smith County, they moved to Covington County, where they settled on a ridge south of the Hollow in the Oakohay area. Here, they established a prosperous community called Hopewell.

By 1880, thirty-year-old Charlie and twenty-eight-year old Laura lived in the Oakohay District. Four children lived with them: George (Laura’s son by Peter Dahmer), age 10; [Roxanne] Viola, age 7; Bettie, age 5; and Elnathan, age 2. All, including Laura and her son George, were listed as “mulattos” on the 1880 federal manuscript census for Covington County. Living nearby were Charlie Craft’s mother, Melvina, and several siblings.

One night a local white mob filled with home brew surrounded and attacked their home. Both Laura and Charlie were excellent shots. Laura shot and killed one of attackers as they tried to protect their children from the mob and, in so doing, the couple had to flee “the ridge.” Laura’s son, George Dahmer, helped them escape. Upon arriving in the Kelly Settlement, they moved off in the swamps on the Leaf River on the old “William Jenkins Place.”

George Washington Dahmer, father of Vernon Dahmer, son of Laura Barnes Craft and Peter Dahmer, stepson of Charlie Craft. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr

The area commonly known as Kelly Settlement was settled by John Kelly, a white man born in North Carolina about 1750. John and his wife, Amelia, left Hancock County, GA, and arrived in Mississippi in late 1819, settling in Perry County. By 1820, the Kelly household included John, Amelia, sons Green, 16, and Osborne, 18, Osborne’s wife Joene, and nine slaves. Among these slaves were the parents of Sarah, whose descendants later formed Kelly Settlement. Although the 1820 federal manuscript census for Perry County listed no free blacks living in the household of John and Amelia Kelly, descendants claim that Sarah’s folks were not slaves, but free people who accompanied the Kelly family to Mississippi.

After the Civil War, Sarah’s children began to homestead land, marry, and raise children. Working together as they had down on John Kelly’s place, they cleared the land to raise crops, cut timber, and hauled it to the Leaf River by oxen to float it down to the Gulf Coast.

Laura Barnes Craft’s son, George Dahmer, moved to the Kelly community ahead of the rest of the Crafts. In 1895, George married Ellen Louvenia Kelly, the daughter of Warren Kelly and Henrietta McComb. Like his own mother, Laura, Ellen’s mother, Henrietta, was a white child born out of wedlock and given to a black family, the McCombs, to raise. The McCombs were living on the William Jenkins place when the Crafts arrived in Perry County. Ellen Kelly’s father, Warren Kelly, was the mulatto son of Green H. Kelly and the grandson of John Kelly, the original white settler of the area. Warren Kelly’s mother was Sarah, the daughter of John Kelly’s slaves (or perhaps free black servants).

Warren Kelly, son of Green Kelly and Sarah Kelly, father of Ellen Kelly Dahmer, grandfather of Vernon Dahmer. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

It was to this community that Charlie and Laura Barnes Craft fled with the aid of Laura’s son, George Dahmer. According to Wilmer Watts Backstrom (their great granddaughter), Charlie and Laura’s family lived in isolation for many years after being forced out of Covington County; they were prone to violent disagreements and exhibited heated tempers. This family drank heavily with much cursing. They lived down in the swamps isolated from the community until the children were all grown. As the children became adults, they gradually moved out of the swamps, married and had families of their own.

Charlie was employed by Green Kelly as a night watchman on the Leaf River. He died before 1910 in Forrest County, MS. By that year, several of his and Laura’s children were married and living in Kelly Settlement, MS. Although Laura’s name does not appear on the 1910 Census, she was still alive that year. In 1920, she lived with her oldest child, daughter Roxanne Craft Watts, on the Dixie Highway, Forrest County, MS. Laura died on 5 June 1922.

Ellen Louvenia Kelly, wife of George Dahmer, mother of Vernon Dahmer, daughter of Warren and Henrietta McComb Kelly. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

Laura’s son and Charlie’s stepson, George Dahmer, identified as a black man even though his mother and biological father were white, demonstrating how strongly one’s racial identity is shaped by social experience.

George and Ellen Kelly Dahmer were the parents of Vernon Dahmer. George was known as an honest, hardworking man of outstanding integrity, rich in character rather than worldly goods. Like his father, Vernon worked hard and became a successful storekeeper and commercial farmer. Before his tragic death, he served as music director and Sunday school teacher at the Shady Grove Baptist Church, as well as president of the Forrest County Chapter of the NAACP. He and his wife, Ellie Jewell Davis, were the parents of seven sons and one daughter.

Vernon F. Dahmer, Sr. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

Vernon Dahmer’s wife and children: seated left to right, George Weldon, Ellie J., Alvin; standing, left to right, Vernon Jr., Betty Ellen, Harold. Photo courtesy of Vernon Dahmer, Jr.

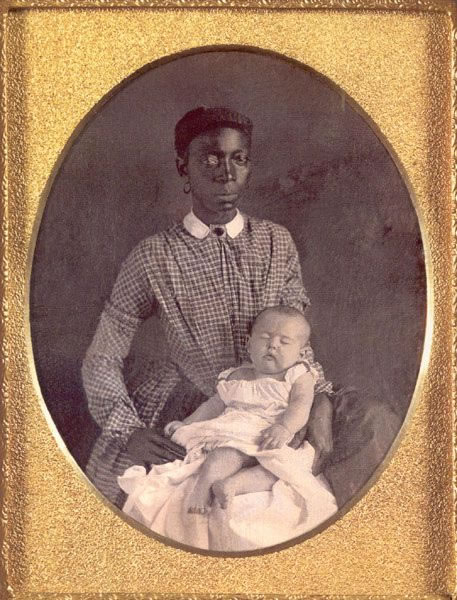

“Negro domestic servant, Atlanta, GA, May 1939.” via

“Negro domestic servant, Atlanta, GA, May 1939.” via

![[Richard DeReef]](https://i0.wp.com/www.gullahtours.com/_derived/dereef.jpg)