I think this article is brilliant and I think that everyone should read it. So, here you go, everyone!

Women and body image: a man’s perspective

Ever wondered why a man can look at an advert featuring a six-pack and laugh, while a woman might look at a photograph of female perfection and fall to pieces? William Leith thinks he might have uncovered the answer

By William Leith

Plenty of guys have told me this story. The guy in question is preparing to go to a party with his girlfriend. She is trying on shoes and dresses. He is telling her how good she looks. She tries on more shoes, more dresses. And then: the sudden, inexplicable meltdown. She crumples on the bed. Something is horribly wrong. Now the party is out of the question.

At this point the other guys will say, ‘Yeah – she looks great.’ And: ‘She looks fine.’ And: ‘I saw her the other day, wearing those shorts.’ And: ‘She is hot.’ Then the first guy will say, ‘That’s what I kept telling her. And that’s when she got really upset. She said, “You just don’t understand.”‘

It’s true – men, by and large, do not understand. In her book The Beauty Myth, Naomi Wolf made this point very powerfully. When a woman has a crisis of confidence about the way she looks there is nothing a man can do to console her.

‘Whatever he says hurts her more,’ says Wolf. ‘If he comforts her by calling the issue trivial, he doesn’t understand. It isn’t trivial at all. If he agrees with her that it’s serious, even worse: he can’t possibly love her, he thinks she’s fat and ugly.’

But it doesn’t stop there, says Wolf. What if the man were to say he loves the woman just as she is – that he loves her for her? An absolute no-no, of course, because then ‘he doesn’t think she’s beautiful’. Worse still, though, if he says he loves her because he thinks she’s beautiful.

There’s no way out. It seems to be, in Wolf’s words, ‘an uninhabitable territory between the sexes’. So why don’t men understand? And, given a bit of education, can the situation be improved?

Well, I’m a man, so let’s see. The first thing to say is that, when it comes to their bodies, men have a completely different attitude. I’m not saying they don’t think about their bodies, or worry about them, because they do. But men relate to their bodies in a simple way.

A man’s body is either fine, or it’s not fine. For a man, the body is a practical object. It’s a machine. Sometimes it works well; sometimes it needs fixing. Some guys know how to fix it, by taking up a sport, maybe, or cutting down on the carbs. Some don’t, and go to seed.

Men see their bodies as machines because, for most of their time on this earth, they have defined themselves as hunters and protectors. They equate being attractive with being strong and fast and muscled. That’s a simple concept, isn’t it? And that simplicity is hard-wired into the male brain.

When his girlfriend has a meltdown, and says she hates her body, that is not a simple concept. Unlike men, women do not have a simple relationship with their bodies. They have a complex relationship with their bodies. This is what men often don’t understand. When it comes to their bodies, women are extremely vulnerable – and, what’s more, lots of people take advantage of that vulnerability. This makes the situation worse.

Men don’t have to contend with this – the hair people, and the make-up people, and the fashion people, and the shoe people, and the bra people, and the nail people, and the eyelash people, and the Botox people, and the cosmetic surgery people, and the perfume people, and the hair-removal people. Oh, and the diet people.

Men are not at the mercy of corporate manipulation on remotely this scale. Sure, there are six-packs creeping into our field of vision every so often. And, sure, this is making us feel insecure. I know – I was fat, and it’s no fun being fat, especially with all those pictures of Brad Pitt nagging away.

And then there are the adverts for Lynx, and the Reebok advert in which a man is chased around town by a big fat hairy belly. But for men the message is very direct. Buy some running shoes. Go to the gym. Cut down on the carbs. For men there is no mystery behind the veil of the adverts. You either tackle the situation, or become a fat slob. End of story.

For men the holy grail is within reach – you just need to get fit, and then you’ll be fine; then you can think about something else. But the messages aimed at women are much more complex and confusing. As the American social commentator Warren Farrell has pointed out, women’s magazines often contain articles about being Superwoman, which are next to adverts about being Cinderella.

In other words, the words tell women how to be independent and in control. But the adverts, where the money is, tell them they have to be beautiful.

Farrell said this more than two decades ago – and, shockingly, nothing has changed. There’s a solid pulse running through everything our culture aims at women – be beautiful, be beautiful, be beautiful.

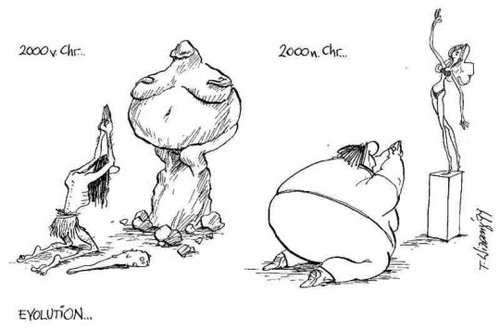

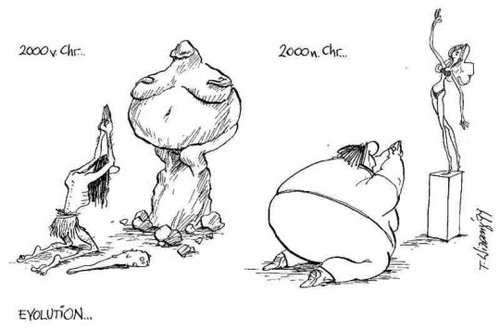

But being beautiful, it turns out, is a near-impossible task. It keeps getting harder and harder. Everybody knows that it entails being slim – and every year the ideal gets slimmer and slimmer. In 1960 the average model weighed 10 per cent less than the average woman. Now she weighs 25 per cent less. Soon she will weigh 30 per cent less. But she doesn’t have the breasts of a skinny woman – nor, as Susie Orbach has recently pointed out, the bottom. To achieve the ideal is vanishingly impossible.

And it’s getting worse. Orbach believes that we are exposed, on a weekly basis, to several thousand images that have been digitally manipulated. And this, in turn, makes more women opt for cosmetic surgery – which, of course, moves the goalposts even farther away.

When lots of people have surgery to make themselves look more beautiful this has the effect of making everybody else feel less beautiful. And this is happening on a global scale – in 2007 people spent £9 billion on cosmetic surgery; the vast majority of them, of course, were women.

So: men are told they should aspire to fitness and strength, and women are told they should aspire to something more nebulous. But that still does not explain, in terms a man could understand, why the female message is so much more powerful and disturbing.

It doesn’t explain why a tenth of women are anorexic, why a growing number are bulimic, why almost half of women, at any given time, are on a diet. It doesn’t quite explain the meltdowns. And it doesn’t explain why women want to be so skinny. Why they think they are fat, when they are not. It doesn’t explain why, when a woman’s body is perfectly attractive, she often thinks it isn’t, and can’t be persuaded otherwise.

In short, it does not explain why a man can look at an advert featuring a six-pack and laugh at it, whereas a woman might look at a picture of Gisele Bündchen and feel a sense of unease that hangs around for days.

John Updike once said that the female body is the world’s prime aesthetic object – we look at it more than we look at anything else, including landscapes, gadgets, cars. In fact, cars and gadgets are often designed to resemble the female body, and landscapes can be painted to remind us of it. When we talk about ‘the nude’ in art we are almost certainly referring to the female nude. As far as nudes are concerned, the male nude is a distant runner-up.

I once wrote the introduction to a book of male nudes by the photographer Rankin; it was a sequel to his previous book of female nudes. One thing struck me above all – male nudes were a much, much harder thing to portray than female ones.

That’s because the female body carries with it a huge weight of iconic significance – thousands of years of being looked at. The female body has meaning. Pictures of the female body can be profound, serious and complex. For thousands of years they have been depicted with reverence. Now imagine having one of those bodies. It puts a bit of pressure on, doesn’t it?

Now I’m beginning to see why women might be so addicted to perfection. They have a lot to live up to – a couple of thousand years of art history, and a couple of thousand airbrushed boobs and bums to deal with every week.

But what started this off in the first place? Why aren’t there so many airbrushed pictures of men around? Of course, these pictures do exist, and their numbers are increasing. But why are women so much more vulnerable to pictures of perfect bodies than men?

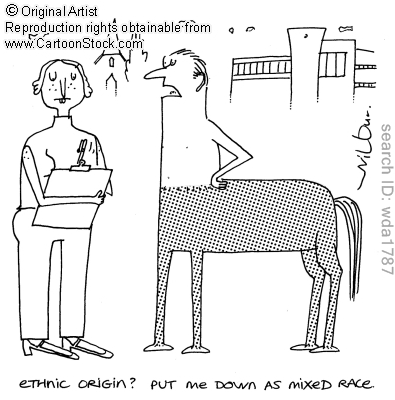

In his book The Evolution of Desire, the American psychologist David Buss goes some way towards explaining why this should be so. Since the Stone Age, he explains, men and women have had different attitudes towards sex. Men can pass on their genes with very little risk – all they need is a fertile woman.

But it’s different for women, because pregnancy is incredibly risky. What women need is a man who looks like a good provider – better still, who looks like a proven provider.

So let’s think about our Stone Age man and woman. If he’s going to settle down, and stop playing the field, he wants one thing above all – a woman who looks fertile. More than that, he wants a woman who looks as if she’ll be fertile for many years to come. In other words, he might consider being a provider and protector, as long as his mate looks young, fertile and unblemished.

And now consider his mate. What does she want? Not just a man who is a good hunter and a good fighter, but a man who has a track record as a hunter and fighter. In other words, an older man. And this is not only true of Stone Age couples. In a survey conducted by David Buss, 10,000 people, in 37 cultures, were polled. ‘In all 37 cultures included in the international study on choosing a mate,’ writes Buss, ‘women prefer men who are older than they are.’

Now I’m getting close to understanding why women are so critical of their bodies. Since prehistoric times they have had a hard-wired link to how they look. For tens of thousands of years it was crucial; it could be the difference between having a protector and not having one – between life and death, even.

For men it’s not the same at all. The odd wrinkle or grey hair doesn’t matter. Hell, it might even be an advantage. As long as you’re good at throwing spears and building shelters, you’ll be fine.

Twenty thousand years on, what has changed? Well, as David Buss points out, it’s unlikely that a Stone Age man would have seen ‘hundreds or even dozens of attractive women in that environment’. But now, when he looks at a Playboycentrefold, he is seeing a woman who has competed with thousands of other women for the part – not only that, he’s seeing the best picture out of thousands.

And it’s not just centrefolds, is it? Just look at newsreaders – mostly, it’s a pretty girl and a grey-haired man. Message to men: relax. Message to women: panic! And then there are the girl groups, and the short-skirted girl onCountdown, and even the characters in the Harry Potter films, where the boys are allowed to look like geeks but the girl must look like a model.

As the art critic John Berger wrote: ‘Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only the relations of men to women, but the relation of women to themselves.’ It’s a tough one, isn’t it?

Surely guys can understand that, at least. If it happened to us, we’d have a meltdown, too.

SOURCE

Large, jovial Grover Cleveland – also known as “Uncle Jumbo” – enjoyed his beer. In 1870 (15 years before he became president), Grover ran for district attorney of Erie County, New York, against Lyman K. Bass. It was a friendly contest. In fact, it was so friendly that Cleveland and his opponent drank and chatted together daily. In the interest of moderation, they agreed to have no more than four glasses of beer per day. But soon they exceeded that and started “borrowing” glasses from the next day and the next day until they’d exhausted their ration for the whole campaign – with the election still weeks away. The solution: Each brought his own giant tankard to the tavern, called it a “glass,” and went back to the four-a-day ration.

Large, jovial Grover Cleveland – also known as “Uncle Jumbo” – enjoyed his beer. In 1870 (15 years before he became president), Grover ran for district attorney of Erie County, New York, against Lyman K. Bass. It was a friendly contest. In fact, it was so friendly that Cleveland and his opponent drank and chatted together daily. In the interest of moderation, they agreed to have no more than four glasses of beer per day. But soon they exceeded that and started “borrowing” glasses from the next day and the next day until they’d exhausted their ration for the whole campaign – with the election still weeks away. The solution: Each brought his own giant tankard to the tavern, called it a “glass,” and went back to the four-a-day ration. The standard scoop on Teddy Roosevelt was that he was a scrawny, sickly weakling from New York City who built himself up into a rough, tough cowboy type through vigorous outdoor pursuits. What’s seldom mentioned is that Roosevelt went from skinny boy to robust young man to plump (though vigorous) president to obese (though still active) ex-president. While running on the Bull Moose Party ticket in a 1912 attempt to regain the White House, Roosevelt was described as “an eager and valiant trencherman” (it meant he ate a lot). If the main course was roast chicken, TR would consume an entire bird himself, in addition to the rest of the meal. Not to mention the four glasses of whole milk the portly prez routinely threw back with dinner. Photos and films show an aging Roosevelt carrying a decidedly wide load.

The standard scoop on Teddy Roosevelt was that he was a scrawny, sickly weakling from New York City who built himself up into a rough, tough cowboy type through vigorous outdoor pursuits. What’s seldom mentioned is that Roosevelt went from skinny boy to robust young man to plump (though vigorous) president to obese (though still active) ex-president. While running on the Bull Moose Party ticket in a 1912 attempt to regain the White House, Roosevelt was described as “an eager and valiant trencherman” (it meant he ate a lot). If the main course was roast chicken, TR would consume an entire bird himself, in addition to the rest of the meal. Not to mention the four glasses of whole milk the portly prez routinely threw back with dinner. Photos and films show an aging Roosevelt carrying a decidedly wide load. William Howard Taft often dieted because his doctor and his wife told the 290-pound president that he must. But without supervision, Will “the Thrill” didn’t just give in to temptation, he sought it. Once while traveling he asked a railroad conductor for a late-night snack. When the conductor said there was no dining car, Taft angrily called for his secretary, Charles D. Norton, who had probably – under instruction from Mrs. Taft – arranged for the diner to be unhooked. Norton reminded the president that his doctor discouraged between-meal eating. Taft would have none of it. He ordered a stocked dining car attached at the next stop and specified that it have filet mignon. “What’s the use of being president,” he said to Norton, “if you can’t have a train with a diner on it?”

William Howard Taft often dieted because his doctor and his wife told the 290-pound president that he must. But without supervision, Will “the Thrill” didn’t just give in to temptation, he sought it. Once while traveling he asked a railroad conductor for a late-night snack. When the conductor said there was no dining car, Taft angrily called for his secretary, Charles D. Norton, who had probably – under instruction from Mrs. Taft – arranged for the diner to be unhooked. Norton reminded the president that his doctor discouraged between-meal eating. Taft would have none of it. He ordered a stocked dining car attached at the next stop and specified that it have filet mignon. “What’s the use of being president,” he said to Norton, “if you can’t have a train with a diner on it?” President Bill Clinton, who famously frequented McDonald’s, was known for eating whatever was put in front of him. He showed a more discriminating, if just as hungry, side in the company of Germany’s chancellor Helmut Kohl, though. Kohl was called “Colossus,” at least in part because he carried 350 pounds on his 6-foot-4 frame. But, in Kohl, Clinton found a gourmand soul mate. In 1994, Clinton hosted the chancellor at Filomena Ristorante of Georgetown for a lunch at which both consumed mass quantities of ravioli, calamari, and red wine, as well as plenty of antipasto, buttered breadsticks, Tuscan white bean soup, salad, and sweet zabaglione with berries. Each ended the meal by ordering a large piece of chocolate cake to go. Clinton once remarked that he and his German counterpart, though the largest of world leaders, were still too slim to be sumo wrestlers.

President Bill Clinton, who famously frequented McDonald’s, was known for eating whatever was put in front of him. He showed a more discriminating, if just as hungry, side in the company of Germany’s chancellor Helmut Kohl, though. Kohl was called “Colossus,” at least in part because he carried 350 pounds on his 6-foot-4 frame. But, in Kohl, Clinton found a gourmand soul mate. In 1994, Clinton hosted the chancellor at Filomena Ristorante of Georgetown for a lunch at which both consumed mass quantities of ravioli, calamari, and red wine, as well as plenty of antipasto, buttered breadsticks, Tuscan white bean soup, salad, and sweet zabaglione with berries. Each ended the meal by ordering a large piece of chocolate cake to go. Clinton once remarked that he and his German counterpart, though the largest of world leaders, were still too slim to be sumo wrestlers.