Category Archives: famixed

speaking of drake…

I’m super-curious about this guy and am itching to know more about the experiential intricacies of his Black/Jewish upbringing, and how he reflects on all of that from where he sits currently as the “New Jew in Hip-Hop.” I don’t think this is a direct quote from Drake, but it rings true: “Finally, his outsider background has become an asset.” That’s exactly how I feel about my own self and I wouldn’t be surprised if a multitude of biracials are emerging into the same space of appreciation for the experience and are cultivating ways to make use of it in a world that was not ready to handle our truth before. Some still aren’t ready. Look out, some!

The New Face of Hip-Hop

By JON CARAMANICA

For most of his teenage years Drake, tall, broad and handsome, was still known as Aubrey Graham (Drake is his middle name) and played the basketball star Jimmy Brooks on the popular Canadian teenage drama “Degrassi: The Next Generation.” In the last 18 months, though, he’s become the most important and innovative new figure in hip-hop, and an unlikely one at that. Biracial Jewish-Canadian former child actors don’t have a track record of success in the American rap industry.

But when “Thank Me Later” (Aspire/Young Money/Cash Money) is released this week, it will cement Drake’s place among hip-hop’s elite. It’s a moody, entrancing and emotionally articulate album that shows off Drake’s depth as a rapper, a singer and a songwriter, without sacrificing accessibility. That he does all those things well marks him as an adept student of the last 15 years: there’s Jay-Z’s attention to detail, Kanye West’s gift for melody, Lil Wayne’s street-wise pop savvy.

In rapid fashion Drake has become part of hip-hop’s DNA, leapfrogging any number of more established rappers. “I’m where I truly deserve to be,” Drake said over quesadillas at the hotel’s lobby bar. “I believe in myself, in my presence, enough that I don’t feel small in Jay’s presence. I don’t feel small in Wayne’s presence.”

But “Thank Me Later” is fluent enough in hip-hop’s traditions deftly to abandon them altogether in places. Finally his outsider background has become an asset. As a rapper, Drake manages to balance vulnerability and arrogance in equal measure, a rare feat. He also sings — not with technological assistance, as other rappers do, but expertly.

Then there’s his subject matter: not violence or drugs or street-corner bravado. Instead emotions are what fuel Drake, 23, who has an almost pathological gift for connection. Great eye contact. Easy smile. Evident intelligence. Quick to ask questions. “He’s a kid that can really work the room, whatever the room,” said his mother, Sandi Graham. “Thank Me Later” has its share of bluster, but is more notable for its regret, its ache.

As for Ms. Berry’s cousin, Drake’s interested, of course, but wary. “I think I have to live this life for a little bit longer before I even know what love is in this atmosphere,” he said. More fame only means less feeling, he knows.

Dodging vulnerability has been a fact of Drake’s life since childhood. His parents split when he was 3. An only child, he lived with his mother, who soon began battling rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that eventually prevented her from working, forcing Drake to become responsible at a young age. “We would have this little drill where, Lord forbid something happened, if there was a fire or an emergency, he would have to run outside and get a neighbor and call 911,” Ms. Graham said. His father, Dennis, who is black, was an intermittent presence — sometimes struggling with drugs, sometimes in jail.

“One thing I wasn’t was sheltered from the pains of adulthood,” Drake said. When something upset him as a teenager, he often told himself: “That’s just the right now. I can change that. I can change anything. The hand that was dealt doesn’t exist to me.’ ”

From an early age he’d been interested in performing, whether rewriting the lyrics to “Mary Had a Little Lamb” or spending time as a child model. By then, he and his mother were living in Forest Hill, a well-to-do, heavily Jewish neighborhood on the north side of Toronto, where he attended local schools, often the only black student in sight. His mother is white and Jewish, and Drake had a bar mitzvah. At school he struggled academically and socially. “Character-building moments, but not great memories,” he recalled. In eighth grade he got an agent and was soon sent off to audition for “Degrassi: The Next Generation,” an updated version of the popular 1980s Canadian drama.

He auditioned after school, on the same day, he said, that he first smoked pot from a bong. Nevertheless he landed the role of the wealthy, well-liked basketball star Jimmy Brooks, who was originally conceived as a white football player.

“Part of his journey is trying to figure where he does fit in in the world, having a white Jewish mom and a black, often absentee father,” said Linda Schuyler, a creator of the show. “It’s almost a comfort factor with Jimmy Brooks. That was the antithesis of his life at the time. It was probably reassuring and a bit escapist for him to play that role.”

Sometimes he was hiding even when the cameras were off, sleeping on the show’s set. “When I woke up in the morning, I was still the guy that could act and laugh,” he said. “It’s just that home was overwhelming.” Along with “Degrassi” came a new, more diverse school closer to the set, where he first tried rapping in public. As he got older, he also tried out his verses on one of his father’s jailhouse friends, who listened over the phone…

yay, shakespeare in the park

I’m thrilled to know that The Public Theater is once again “putting this mosaic out into the world.” And that Ruben Santiago-Hudson has biracial kids. And that he speaks openly about it. Actually that’s not extraordinary, but I didn’t know that about him before. I love The Winter’s Tale. My favorite monologue is in it. If I weren’t too persnickety to wait in line for hours for tickets, I would be sure to see this. However, it’s not gonna happen. My loss, I’m sure. Just for clarification, the “yay” is for depicting a “non-traditional” marriage/family. Not for Hudson marrying a Swede and having mixed kids. Although I like that a lot too.

Actor Ruben Santiago-Hudson and his twins Trey and Lily attended the “Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals” film premiere on February 17, 2010 in Westwood, California.

Ruben Santiago-Hudson Tells the Tale

The actor discusses starring in the Shakespeare in the Park production of The Winter’s Tale.

Ruben Santiago-Hudson has been the epitome of excellence for over 30 years; winning a Tony Award for Seven Guitars, numerous honors for the HBO adaptation of his acclaimed solo play Lackawanna Blues, and plaudits for his direction of several shows including Things of Dry Hours and The First Breeze of Summer. This summer, he’s starring in the Public Theater’s Shakespeare in the Park production of The Winter’s Tale, and in the fall, he’ll be back co-starring on ABC’s hit crime drama Castle. TheaterMania recently spoke with Santiago-Hudson about these projects.

THEATERMANIA: What made you want to do The Winter’s Tale this summer rather than just take a nice breather between shooting Castle?

RUBEN SANTIAGO-HUDSON: I just love the challenge of doing Shakespeare. I am part of the Public Theater family and I got a call to look at the play, and before I could even finish it, I said I’d love to do it.

TM: Your character, Leontes, is considered one of the most difficult in the canon, since you accuse your wife and best friend of infidelity without any seeming cause. How do you justify that?

RSH: It is a challenge to make that action comprehensible to the audience. But I look at the text. Polixenses may be my friend, but he’s stayed with my family for nine months — and I think if anyone stayed that long at my house, I’d find fault with them. And I am sure over that time, Leontes has seen some glimpses of unusual behavior — perhaps wearing less clothing around each other or laughing too loud.

TM: Still, you cause your wife to kill herself and banish your infant daughter. How is the audience supposed to sympathize with that?

RSH: I hope the audience sees that I balance my cruelty with much love and that my actions came from defending my honor and that my rage is from jealousy and madness. It’s important that I am not just being the stereotypical angry black man. And when it all comes clear, I’m the most penitent person — I’m almost a saint by the end of the play.

TM: As is typical of many productions at the Public, the cast is completely multi-racial. For example, your wife, Hermoine, is being played by Linda Emond, who is white. What are your thoughts about this?

RSH: I think it reflects the mirror of modern society. When you look in the newspaper, you see Sandra Bullock with a black child. And this play reflects what my real family looks like — my wife is Swedish and our children are biracial — so it’s great to put out this mosaic to the world. And I think we should put the best artists we can on stage, and what I love about the Public Theater’s audience is they feel the same way. They don’t care if the king is black and the queen is white; they’re out there to see this play done well.

Linda Emond and Ruben Santiago-Hudson

in rehearsal for The Winter’s Tale

(© Nella Vera)

“kinds” of biracial

Fantastic commentary on something that I totally missed in the media. I honestly don’t know who Drake is. I’ll look him up in a sec…. Oh. I see. Anyway, Whitney Teal makes such great points here (a fav being that one would never compare G.W. Bush to Eminem), and has me wanting to make a list of all the “kinds of biracial” that I can imagine. And then I want to study the intricacies of the experiences that molded the various varieties of biracialness. I love biracial. It never gets old for me. I suppose you can call me Captain Obvious for that statement.

Is One Mulatto the Same as the Next?

By Whitney Teal

Has the election of President Obama changed the way we think about biracial people in this country? I’d argue that it’s questionable. Especially when people are drawing comparisons between the prez — a half-white, half-Kenyan, Ivy League-educated lawyer — and Aubrey Graham, otherwise known as Drake, who is a half-Jewish and half-African-American entertainer from Canada. Yeah, I don’t see the similarities either.

thomas chatterton williams

But TheRoot.com contributor Thomas Chatterton Williams, who describes himself as the son of a black father and a white mother,” seems to think that the two mulattoes (his word, not mine) deserve a comparison. Yes, Williams thinks that it’s helpful to compare a Canadian rapper and the President (as he puts it, one of the “most visible mulattoes living and working today”). And he’s not alone, either. A few months back, a couple of my Twitter friends and I ripped Chester French band member David-Andrew ‘D.A.’ Wallach a new one for tweeting that he was discussing “all the similarities” between the two men. When I asked him to explain himself, he replied, “For one, I think they’re both extremely studied.” Womp, womp, cop-out. Lots of men are studied. President Obama and Drake are both, simply, biracial. And they’re not even the same “kind” biracial either, but that doesn’t seem to make a difference.

When I showed my sister the story on The Root, she screamed (via Google Messenger) and replied, “Obama and Drake in the same sentence? Do people mention [President] Bush and Eminem in the same sentence?” She’s right. White men are allowed to choose their own identities. Black men not so much, and biracial men certainly not. Which begs the question, why can’t we see that one biracial person is not the same as the next?

In general, polite company, we as general, polite people, recognize that a person’s experiences are not solely dictated by their race or ethnicity. For example, I don’t think people considering Lucy Liu, a famous actress, and Connie Chung, an award-winning journalist, would try and argue that the two have much in common, at least on the surface. The same with Denzel Washington and Reggie Bush, or Barbara Streisand and Heidi Fleiss. No comparisons. But people, general and polite as they are, still seem to view the experiences of biracial people in this country as singular in nature.

And often, as The Root essay explores, polarizing. “Mixed-race blacks […] are the physical incarnation of a racial dilemma that all blacks inevitably must confront: To sell out or keep it real? That is the question,” writes Williams, who spends the better part of 1,000 words waxing on about the definition of authentic blackness (or at least how he sees it). According to Williams, a mixed-race person must choose to be black, like the president and like Drake, who “both proudly define themselves as black.” A mixed-race person must then “act black,” which Williams sees as wearing loose clothes and playing basketball.

If blackness meant just one thing, and if mixed-race people were able to align themselves with just one part of their identity, then his essay might hold more weight. But black people don’t have just one identity, at least not to ourselves. Hollywood directors, novelists and journalists may see us as trash-talking, saggy pant-wearing basketball fanatics, but I don’t think that’s how we see ourselves. And by asserting that he can turn his black switch on and off, simply by altering the fit of his pants, Williams — though he may identify as black — shows how much he doesn’t understand the complexity of black culture.

Which is why I don’t believe that we should automatically label mixed-race people as black; they’re mixed-race. Being biracial may be similar to African-American culture, just as West African and West Indian cultures share similarities to black culture, but ultimately have their own dialects, dress, worship practices, food and courtship rituals. But biracial people etch out their own identities. Sure, they may be similar to that of African-Americans or other cultures. But it’s limiting to both black and biracial people when society automatically labels anyone with brown skin and textured hair black. Whether we’re talking about President Obama or anyone else, what it means to be biracial is an entirely individual question.

offensive or no?

Upon reading the headline of the article my mom emailed me, I was all set to be very offended by these photos. After reading it and seeing the pics, I am not offended. Is that bad? When I read “blackface” I think poorly applied shoe polish and outrageously red lipstick. When I saw these pictures and read Schiffer’s statement that they were playing with different men’s fantasies, I thought it made sense. Lagerfeld and Dom Perignon hired one super Supermodel to play two characters (for lack of a better analogy). To me this is not offensive. I don’t think Schiffer kept a black model from working that day. What if Naomi Campbell had done the ad in “whiteface”? Would that be offensive? I also wonder if Heidi Klum would have agreed to participate in this. I would love to get her take on it.

Claudia Schiffer strikes controversial pose in ‘blackface’ for German magazine

BY MEENA HARTENSTEIN

DAILY NEWS STAFF WRITER

Claudia Schiffer is one of the world’s best-loved supermodels, but she’s drawing a firestorm of criticism for her latest magazine cover.

The blond stunner is at the center of a racially-charged controversy after a photo of her in “blackface” hit the Internet this month.

In the photo, which was shot by Karl Lagerfeld two years ago as part of an ad campaign for Dom Perignon, Schiffer is disguised in an Afro wig and dark face paint, prompting accusations of insensitivity.

“It shows poor taste and it’s offensive,” Shevelle Rhule, fashion editor at black lifestyle magazine Pride, told U.K.’s Daily Mail. “There are not enough women of color featured in mainstream magazines. This just suggests you can counteract the problem by using white models.”

The photo resurfaced when German magazine Stern Fotografie repurposed the image as one of six hardback covers for its 60th anniversary issue.

The other covers also feature Schiffer in various costumed looks shot by Lagerfeld – as a sexy secretary, a leather-clad cop, Marie Antoinette, and even an Asian woman in a kimono.

Schiffer’s rep defended the series, saying, “The pictures have been taken out of context. The images were designed to reflect different men’s fantasies. The pictures were not intended to offend.

Read more HERE

rue mcclanahan, farewell

sad, but unfortunately not shocking

best for last

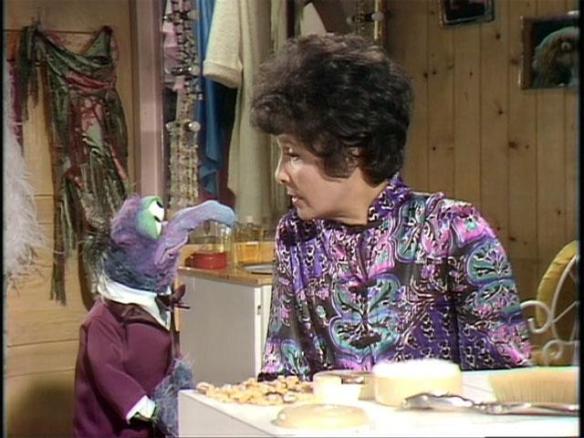

The following will come as no surprise to you if you’ve been keeping up with this blog for the last year. At least I think all of those Jim Henson posts were done last May… I have a hard time keeping track of this thing.

This is ‘fly in my soup’ guy, right? Love him!

This is ‘fly in my soup’ guy, right? Love him!

Circa 1976. A very special year. Loving the color coordination.

Circa 1976. A very special year. Loving the color coordination.

Stahs in the sky!

the worst kind of acceptance

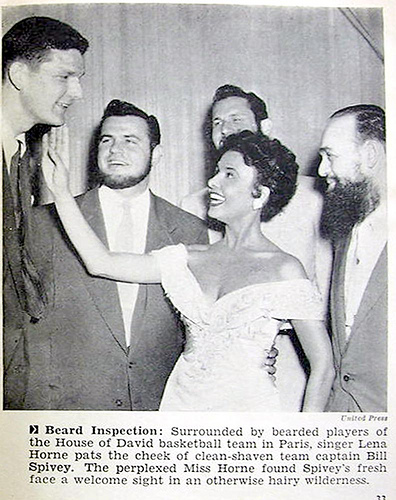

I’m going to try to get all of this Lena stuff out of my system today. It’ll actually never be out of my system, but as far as blogging goes… you know what I mean. I really enjoyed the following NPR blog post focusing on the racialization of Ms. Lena Horne. I wonder how different things would have been for her if things would have been different.

Lena Horne: Of Race And Acceptance

by PATRICK JARENWATTANANON

In the reports of Lena Horne’s death that have emerged so far, much has been made of the fact that she was a black woman in an age of popular entertainment dominated by white faces. Her talent was obvious, but her skin hampered her attempts to become a major movie star, assigning her to bit parts that could be removed for Southern audiences.

Eventually, after the civil rights movement, Horne would be recognized as an entertainment icon. Her work as a jazz singer, theatre performer and television actress did much for that legacy, as well. But she also knew that the skin color that worked against her also worked for her. In the obituary that came over the AP wire, she is quoted as saying this:

“I was unique in that I was a kind of black that white people could accept,” she once said. “I was their daydream. I had the worst kind of acceptance, because it was never for how great I was or what I contributed. It was because of the way I looked.”

“A kind of black that white people could accept.” Think on that for a moment, and beyond the idea of being a light-skinned African-American. You could write the entire history of jazz through that lens.

Jazz’s early black stars (Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Nat “King” Cole, Billie Holiday and others) worked overtime to be somehow disarming, or mythologized, or otherwise acceptable to white bourgeois audiences. Meanwhile, the music they and all their colleagues were making was popularized by white musicians — Paul Whiteman, Benny Goodman, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the Dorsey Brothers — sometimes well, sometimes drained of its swing energy. This continuing process is a big part of jazz’s transformation from scourge of society into America’s classical music.

Indeed, the entire cultural history of the U.S. in the 20th century could be viewed like that. Even today, where ethnic identity comes in many more shades, the middle-class white audience still plays arbiter and co-opter of what hits the mainstream. That’s admittedly a reductive viewpoint, ignoring the powerful experience of the art created, and perhaps it’s a bit cynical, too. But it would be true to Lena Horne’s experience, both marginalized and a trailblazer for who she, biologically, was.

So what’s to do about this? Can’t we just remember Horne as a great singer and actress, the woman who did “Stormy Weather,” and the person whose friendship with Billy Strayhorn brought out the best in both of them?

Sure, but I’d rather not do only that. For one, it negates how she stood up against demeaning portrayals in what roles she took, and how she spoke out strongly against discrimination throughout her career. By omitting all that from our narrative of her life, it allows even the most well-meaning of people to conveniently forget how racism profoundly shaped the creation, marketing and embrace of American art, and continues to do so today.

The New York Times‘ obituary has another illustrative quotation:

My identity is very clear to me now. I am a black woman. I’m free. I no longer have to be a ‘credit.’ I don’t have to be a symbol to anybody; I don’t have to be a first to anybody. I don’t have to be an imitation of a white woman that Hollywood sort of hoped I’d become. I’m me, and I’m like nobody else.

Lena Horne didn’t choose to be racialized based on her genetic assignment, but she was. Remarkably, she ran with it, using it as a source of strength and pride and artistic inspiration. That’s worth remembering, to0.

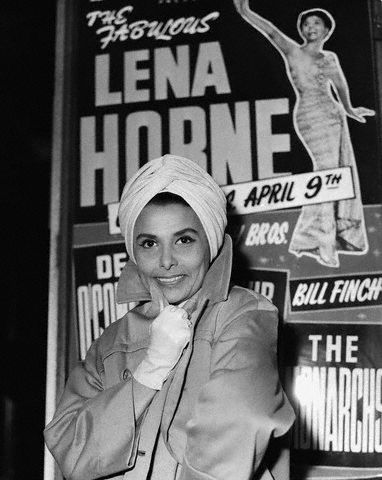

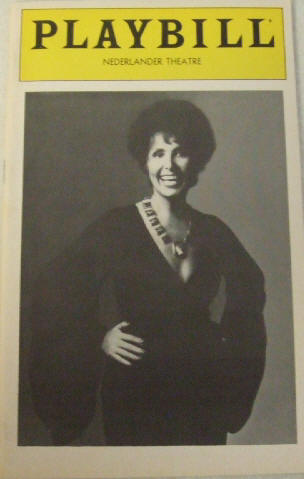

goodbye, lena

I am deeply saddened by the loss of the legendary Lena Horne. I don’t think I have much personal commentary at this moment. I met Lena Horne once. I was four or five. My mom had a friend in Ms. Horne’s Broadway show.

She took me to see it. We went backstage. My mom says that with Lena and I it was love at first sight. From what I can recall, I agree. On my end anyway. When I think back on that night the images that come up are all glowy and glittery with a hazy quality. Almost like a dream. Lena was truly magical. She seemed to think I was as well. Heck, when I was four or five I thought I was magical, too. Or, should I say that I knew I was. That I hadn’t forgotten. And nobody had tried to tell me otherwise yet. I imagine now that Lena sprinkled some kind of fairy dust on me with a whisper never to forget who I am. Not any part of it. Especially not the magic.

I digress.

Needless to say I am extremely grateful to my mother and to Vondie and to Lena for that moment. And also to Lena for breaking down barriers and speaking out against injustices and for paving the way for me to stand here today thinking these thoughts and trying to be a beacon for positive social change.

via The Huffington Post

Singer Dies At 92

NEW YORK — Lena Horne, the enchanting jazz singer and actress known for her plaintive, signature song “Stormy Weather” and for her triumph over the bigotry that allowed her to entertain white audiences but not socialize with them, has died. She was 92.

Horne died Sunday at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, said hospital spokeswoman Gloria Chin, who would not release details.

Quincy Jones, a longtime friend and collaborator, was among those mourning her death Monday. He called her a “pioneering groundbreaker.”

“Our friendship dated back more than 50 years and continued up until the last moment, her inner and outer beauty immediately bonding us forever,” said Jones, who noted that they worked together on the film “The Wiz” and a Grammy-winning live album.

“Lena Horne was a pioneering groundbreaker, making inroads into a world that had never before been explored by African-American women, and she did it on her own terms,” he added. “Our nation and the world has lost one of the great artistic icons of the 20th century. There will never be another like Lena Horne and I will miss her deeply.”

“I knew her from the time I was born, and whenever I needed anything she was there. She was funny, sophisticated and truly one of a kind. We lost an original. Thank you Lena,” Liza Minnelli said Monday. Her father, director Vincente Minnelli, brought Horne to Hollywood to star in “Cabin in the Sky,” in 1943.

Horne, whose striking beauty often overshadowed her talent and artistry, was remarkably candid about the underlying reason for her success: “I was unique in that I was a kind of black that white people could accept,” she once said. “I was their daydream. I had the worst kind of acceptance because it was never for how great I was or what I contributed. It was because of the way I looked.”

In the 1940s, Horne was one of the first black performers hired to sing with a major white band, to play the Copacabana nightclub in New York City and when she signed with MGM, she was among a handful of black actors to have a contract with a major Hollywood studio.

In 1943, MGM Studios loaned her to 20th Century-Fox to play the role of Selina Rogers in the all-black movie musical “Stormy Weather.” Her rendition of the title song became a major hit and her most famous tune.

Horne had an impressive musical range, from blues and jazz to the sophistication of Rodgers and Hart in such songs as “The Lady Is a Tramp” and “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.” In 1942’s “Panama Hattie,” her first movie with MGM, she sang Cole Porter’s “Just One of Those Things,” winning critical acclaim.

In her first big Broadway success, as the star of “Jamaica” in 1957, reviewer Richard Watts Jr. called her “one of the incomparable performers of our time.” Songwriter Buddy de Sylva dubbed her “the best female singer of songs.”

“It’s just a great loss,” said Janet Jackson in an interview on Monday. “She brought much joy into everyone’s lives – even the younger generations, younger than myself. She was such a great talent. She opened up such doors for artists like myself.”

Horne was perpetually frustrated with racism.

“I was always battling the system to try to get to be with my people. Finally, I wouldn’t work for places that kept us out. … It was a damn fight everywhere I was, every place I worked, in New York, in Hollywood, all over the world,” she said in Brian Lanker’s book “I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America.”

While at MGM, Horne starred in the all-black “Cabin in the Sky,” but in most movies, she appeared only in musical numbers that could be cut when shown in the South and she was denied major roles and speaking parts. Horne, who had appeared in the role of Julie in a “Show Boat” scene in a 1946 movie about Jerome Kern, seemed a logical choice for the 1951 movie, but the part went to a white actress, Ava Gardner, who did not sing.

“Metro’s cowardice deprived the musical (genre) of one of the great singing actresses,” film historian John Kobal wrote.

“She was a very angry woman,” said film critic-author-documentarian Richard Schickel, who worked with Horne on her 1965 autobiography.

“It’s something that shaped her life to a very high degree. She was a woman who had a very powerful desire to lead her own life, to not be cautious and to speak out. And she was a woman, also, who felt in her career that she had been held back by the issue of race. So she had a lot of anger and disappointment about that.”

Early in her career, Horne cultivated an aloof style out of self-preservation. Later, she embraced activism, breaking loose as a voice for civil rights and as an artist. In the last decades of her life, she rode a new wave of popularity as a revered icon of American popular music.

Her 1981 one-woman Broadway show, “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music,” won a special Tony Award, and the accompanying album, produced by Jones, earned her two Grammy Awards. (Horne won another Grammy, in 1995 for “An Evening With Lena Horne.”) In it, the 64-year-old singer used two renditions – one straight and the other gut-wrenching – of “Stormy Weather” to give audiences a glimpse of the spiritual odyssey of her five-decade career.

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born in Brooklyn on June 30, 1917, to a leading family in black society. Her daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, wrote in her 1986 book “The Hornes: An American Family” that among their relatives was Frank Horne, an adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

She was largely raised by her grandparents as her mother, Edna Horne, who pursued a career in show business and father Teddy Horne separated. Lena dropped out of high school at age 16 and joined the chorus line at the Cotton Club, the fabled Harlem night spot where the entertainers were black and the clientele white. She left the club in 1935 to tour with Noble Sissle’s orchestra, billed as Helena Horne, the name she continued using when she joined Charlie Barnet’s white orchestra in 1940.

A movie offer from MGM came when she headlined a show at the Little Troc nightclub with the Katherine Dunham dancers in 1942.

Her success led some blacks to accuse Horne of trying to “pass” in a white world with her light complexion. Max Factor even developed an “Egyptian” makeup shade especially for her. But she refused to go along with the studio’s efforts to portray her as an exotic Latina.

“I don’t have to be an imitation of a white woman that Hollywood sort of hoped I’d become,” Horne once said. “I’m me, and I’m like nobody else.”

Horne was only 2 when her grandmother, a prominent member of the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, enrolled her in the NAACP. But she avoided activism until 1945 when she was entertaining at an Army base and saw German prisoners of war sitting up front while black American soldiers were consigned to the rear.

That pivotal moment channeled her anger into something useful.

She got involved in various social and political organizations and, partly because of a friendship with singer-actor-activist Paul Robeson, was blacklisted during the red-hunting McCarthy era.

By the 1960s, Horne was one of the most visible celebrities in the civil rights movement, once throwing a lamp at a customer who made a racial slur in a Beverly Hills restaurant and, in 1963, joining 250,000 others in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. Horne also spoke at a rally that year with another civil rights leader, Medgar Evers, just days before his assassination.

The next decade brought her first to a low point, then to a fresh burst of artistry. She appeared in her last movie in 1978, playing Glinda the Good in “The Wiz,” directed by her son-in-law, Sidney Lumet.

Horne had married MGM music director Lennie Hayton, a white man, in Paris in 1947 after her first overseas engagements in France and England. An earlier marriage to Louis J. Jones had ended in divorce in 1944 after producing daughter Gail and a son, Teddy.

“It was in Hollywood that Horne met her second husband, Lennie Hayton, who was also her musical mentor at MGM. He was also white. When the couple announced their marriage in 1950 — three years after it had actually occurred, they were confronted with angry rejection from the Hollywood community. Despite all the difficulties of a racially mixed marriage, their union flourished, lasting from 1947 until Hayton’s death in 1971.”

Her father, her son and Hayton all died in 1970 and 1971, and the grief-stricken singer secluded herself, refusing to perform or even see anyone but her closest friends. One of them, comedian Alan King, took months persuading her to return to the stage, with results that surprised her.

“I looked out and saw a family of brothers and sisters,” she said. “It was a long time, but when it came I truly began to live.”

And she discovered that time had mellowed her bitterness.

“I wouldn’t trade my life for anything,” she said, “because being black made me understand.”