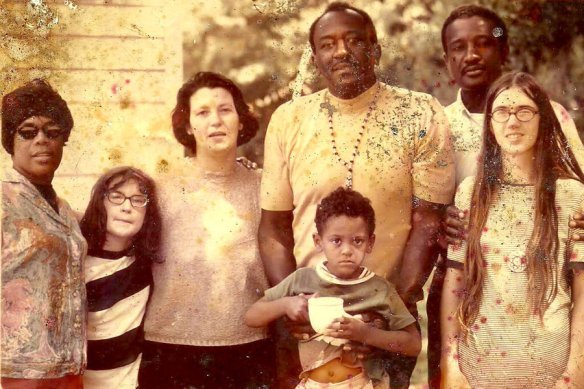

Thank you, Lee, for turning me on to this little “gem.” Horrifying sums it up well. I don’t know what content I find most horrifying. I’m picking up lots of “tragic mulatto” and “jezebel” (the cover page photo!) innuendo though those specific terms aren’t used. In fact, the passers don’t have to be mulatto at all. As I’m constantly told, as a nation and a people we’re all mixed and there are plenty of “black” people that are lighter than some mulattoes such as myself. I do like this notion of “one honest goal: the elimination of the invisible color boundary which for so many years unfairly kept him from his rightful place in the sun.” We’re still workin’ on it.

…it seems well-nigh incredible that some five million Negroes have turned their backs on their own race and are passing as white. For almost a quarter of a century, this fantastic lie has been lived by large groups of Negroes with no sign of abatement despite the strong gains that have been made by the champions of anti-segregation.

In the year 1960 alone more than 60,000 negroes are expected to “disappear”, cross the invisible color line into the world of whites. These are not just dreamed up figures. They are actual facts. Just as it is a fact that no one ever reports a Negro to the Missing Persons Bureau unless they are absolutely sure the missing human isn’t passing.

Many shocking incidents were brought to light some years back in a sensational book, ‘Black Metropolis’ by St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton. The authors claim that many “white negroes” as passers are called— hold strong positions in the white world as physicians, scientists, and public administrators—despite the fact that many such jobs are also held by Negroes unashamed of their race.

The late Walter White, himself a Negro, and one of the prime movers in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, once attempted to clarify the problem of passing. He said: “Negroes naturally resent the loss of some of the brilliant minds which would be an asset to them in their grim struggle for survival. But if any Negro believes he will be happier living as a white and thereby escape the barbs and handicaps of prejudices, or if he believes he can use his ability and training to greater advantage on the other side of the racial line, most Negroes wish him well.”

When it comes to passing, although most Negroes today refuse to condone it, they will not tell on one another. Most seem to understand the reasoning that prompts lighter-hued members of their race wanting to cross over.

“We know there are stronger anti-discrimination laws than ever before,” they will tell you, “but when a negro has a white skin, he seems to have a compulsion to live the way of the people who have so long opposed him. He doesn’t seem to realize that scientists have proven that the very people who condemn him might not be in a position to do so.”

A scientist like those mentioned above is Dr. Caroline Day, of Atlanta University, who wrote in her famous Harvard African Studies: “The grim joke of the whole matter is that for 150 years and more the Negro has been absorbed and his descendants are constantly rubbing elbows with some of the very ones who are discussing them.”

Even the fact that people, who believe all passers are eventually found out because their children are sure to be black, are merely deluding themselves, hasn’t deterred the practise of passing. Science took the inherited color theory apart a long time ago, with the aid of such eminent savants as Amram Schienfeld, Dr. Ernest A. Hooten and the late Dr. Edward M. East, who theorized thus; “If one of the parents is pure white, the baby cannot he darker than the darker parent. If they both have Negro blood, the baby may be slightly darker than its parents hut the chances are against it.”

With the legalization of racial intermarriage approved in some 22 states, nobody has been able to upset their theory – though, obviously, chances to do so have been many.

Yet the “passers” themselves seldom worry about theories. The “permanent passer”, going over the line, never comes back. He prefers to end his days living a big white lie; and women passers who marry bear children and keep their secret for life.

Only under unusual circumstances, such as the one that befell the wife of a prominent socialite, does a sensational exposure ever occur. This was the Leonard Kip Rhinelander case, which rated lurid headlines when the socialite playboy sought to have his marriage to Alice Jones set aside. Rhinelander claimed his wife was colored and failed to tell him so. In her defense, Alice stripped to the waist and bared her breasts to the jury, thus providing the sensation-seeking New York Graphic with a classic composite-photo of this closed door session for its front page.

Besides the “permanent passer”, the “segmental passer” stands without guilt or censure. The “segmental passers” lead a dual life; whites by day, Negroes by night. You’ll often find them in jobs where opposition to Negroes is strong but secret-Some are telephone operators, receptionist, typists, clerks in large corporations and in department stores, where, though some Negroes are employed the unspoken policy is “Enough is enough.”

On Broadway, particularly, the Negro girl has a tough time getting a chorus or showgirl job. There is a story current of a Negro showgirl, allegedly passing as white, who was recognized by a popular Negro singer, but he refused to reveal her secret. He also reportedly wouldn’t talk to the girl, not because of her “passing” but because of her more than passing interest in a white socialite-playboy who met her nightly.

“Obviously she hasn’t learned yet that mixed marriages are no longer looked on with horror,” a Negro artist told INSIDE STORY, “so she’ll go on living her lie and, in the long run, probably find her heart broken because she feels she can’t reveal her secret to the man should he want to marry her. Life will never be easy for her. She not only sometimes has to listen to blasts against her race, but worry every moment about being exposed.”

While there’s no way of truly gauging the number of passers operating, some estimate is arrived at by studies of census reports, immigration records, vital statistics and information from other sources. Yet this does not take into account the ‘’segmental passer” or the passer who, in the past, was known as an “occasional” a reference to light-hued Negroes who occasionally went downtown to segregated areas and, as a lark, spent their money on white entertainment.

Actually, when it comes to “passing”, the shocked might as well face these facts: Passers not only go through life as white, they have children who look (and are) white. Any anthropologist will tell you that if a person has one-sixteenth or less of Negro blood—it is impossible to determine his or her ancestry.

Yet, the practice of passing still continues, much to the chagrin, not necessarily the shame, of the Negro who believes in living as he was born. To such a Negro, there can be only one honest goal: the elimination of the invisible color boundary which for so many years unfairly kept him from his rightful place in the sun. The passer, working in the movies, working as a white actress or a showgirl, or a model or a clerk, or a receptionist doesn’t think of this. He’s thinking of himself. Or herself. And that, to a good many Negroes, is a “shameful secret!