Author Archives: Tiffany

john, how could you?

it’s stories like this that lead to comments (taken from various youtube videos i’ve made) like this :

|

-mixed people r racist and would love 2 blacks extinct and wiped of the planet!

|

|

-Bi racial my ass,these people are black when they get through talking.Stop running from your blackness and them white folks that you are trying lick up under are calling you nigger behind your backs.More videos we see on youtube or myspace,will thousands of video blogs from these coons hating they’re blackness and fronting like they’re special because the have one parent that is white and the other black,that bull shit and these coons know it.

|

|

all i can say/speculate is “sign of the times,” and “survival of the fittest,” and his karma sure did catch up to him in the end…

i wonder if his children were mulatto by virtue of carruthers’ mulatto-ness alone, or was kitty also a mulatto. doesn’t matter. just curious. i also wonder who owned him. it doesn’t seem to be his father or the neighbors whom he apprenticed… maybe it was the father though. i’ve read this four times and just haven’t a clue. ah, history…

John Carruthers Stanly: From Slave to Slave Owner

The story of John Carruthers Stanly, a former slave who gained his freedom, only to become the largest slaveholder in Craven County, North Carolina.

John Carruthers Stanly

1774-1846

Black Slaveholder

Stanly, born a slave in 1774, was the son of an African Ibo woman and the white prominent merchant-shipper John Wright Stanly. He was apprenticed to Alexander and Lydia Stewart, close friends and neighbors of his father. They saw to it that John received an education and learned the trade of barbering. At an early age, they helped him establish his own barbershop in New Bern. Many of the town’s farmers and planters frequented his barbershop for a shave or a trim. As a result, Stanly developed a successful business. By the time he reached the age of twenty-one, literate and economically able to provide for himself, his owners petitioned the Craven County court in 1795 for his emancipation. However, he was not completely satisfied with the ruling of the court and in 1798, through a special act, the state legislature confirmed the emancipation of John Carruthers Stanly, which entitled him to all rights and privileges of a free person.

Between 1800 and 1801, Stanly purchased his slave wife, Kitty, and two mulatto slave children. By March 1805, they were emancipated by the Craven County Superior Court. A few days later, Kitty and Stanly were legally married in New Bern and posted a legal marriage bond in Raleigh. Stanly’s wife was the daughter of Richard and Mary Green and the paternal granddaughter of Amelia Green. Two years later, in 1807, Stanly was successful in getting the court to emancipate his wife’s brother.

Some politically correct Court Historians end the story here, if they acknowledge the existence of black slaveholders at all. What a noble thing, to purchase and emancipate one’s own family! But there is much more to the story.

After securing his own and his family’s freedom, Stanly began to focus more on business matters. He obtained other slaves to work for him. Two of them, Boston and Brister, were taught the barbering trade. Once they became skillful barbers, Stanly let them run the operation while he used the money they helped him earn to invest in additional town property, farmland, and more slaves.

Through his business acumen, Stanley eventually became a very wealthy plantation owner and the largest slaveholder in all of Craven County. He profited from investments in real estate, rental properties, the slave operated barbershop, and plantations from which he sold commodities such as cotton and turpentine.

Stanly’s plantations and rental properties were operated by skilled slaves along with help from some hired free blacks. To improve his rental properties in New Bern, he used skilled slaves and free blacks to build cabins and other residences and to repair and renovate these properties. During the depression of the early 1820s it was slave labor that kept Stanly economically stable.

The 1830 census reveals that Stanly owned, 163 slaves. He has been described as a harsh, profit-minded task master whose treatment of his slaves was no different than the treatment slaves received from white owners. Stanly’s goal, shared by white southern planters, was on expanding his operations and increasing his profits.

During the early 1820s, Stanly’s wife, Kitty, was taken seriously ill. She became bedridden and, despite careful attention by two slave nurses, she died around 1824. It was at this same time that Stanly began to face a series of financial difficulties. His fortune began to plummet when the Bank of New Bern, due to the national bank tightening controls of some state and local banks, was forced to collect all outstanding debts. Unfortunately, Stanly had countersigned a security note for John Stanly, his white half-brother, in the amount of $14,962. Stanly was forced to assume the debt. This, along with his own debts forced him to refinance his mortgages and sell large pieces of property, including slaves. When these options did not resolve his economic woes, he resorted to mortgaging his turpentine, cotton, and corn crops, as well as selling his barbershop, which had been operating continuously for forty years. Without a steady flow of income, his fortunes continued to decline. In 1843, his last 160 acres of land were sold at public auction. Three years later, at the age of 74, John Carruthers Stanly died. At the time of his death he still owned seven slaves.

John Wright Stanly House, New Bern, North Carolina

sambo meets jim crow

i thought this worth sharing. i’ve been questioning myself as to why i keep posting these old negative images… what’s my point?… how is this helping?… i’m not exactly sure, but i think it has something to do with wanting everyone to examine the framework from which our racial paradigm originated. to see how these notions of majority vs. minority (and all of the implications held therein) came to be ingrained into our national subconscious… how they continue to be perpetuated on some level by today’s media/advertising… and how, perhaps, we just take it all for granted… “it’s just the way things are, the way we are”… but it’s all so preposterous… things can be any way we choose to make them, any way we choose to see them… choose to see ourselves and each other…

The Black Conscription.

When Black Meets Black Then Comes the End(?) of War.

Punch, Volume 45, September 26, 1863, p. 129

To modern sensibilities, this is one of the most offensive of Tenniel’s cartoons, as its theme is the notion that black men are incapable of becoming good soldiers. In a (wholly hypothetical) meeting of Union and Confederate black troops on the battlefield, martial ardor dissolves into comic stereotype. The Northern conscript is identifiable by his striped trousers. His Southern counterpart, dressed in a white cotton uniform distinguished only by a capital letter “S” on his belt and bandolier, breaks into an open-mouthed grin and begins to caper as the two clasp hands. Behind them, surrounding their respective flags, representatives of the two black conscript armies socialize with obvious amiability, forgetting all pretense of military discipline. In word balloons, the Northern soldier asks “Dat you Sambo? Yeah, yeah!” while his Southern counterpart responds “Bless my heart, how am you, Jim?”

While the ranks of Northern black regiments ultimately included many “contraband” fugitives from slave states, the earliest black troops (such as the famed 54th Massachusetts) were recruited exclusively from the free black populations of Northern states. Many of these units acquitted themselves bravely on the field of battle. Officially, there was no conscription of blacks as combat soldiers by either side: all were volunteers. While blacks were used by the Southern forces throughout the war in non-combat roles (especially as laborers for tasks such as the construction of fortifications), the raising of black troops to fight for the Confederacy, though proposed cautiously by a few within the military, was vehemently resisted by most Southerners as deleterious to the slave system until the war was almost over. There is no record that the few units of black Confederate soldiers, organized during the final weeks before the fall of Richmond (nearly eighteen months after the publication of this cartoon), ever met black Union troops in combat. The name Sambo, the “characteristic” dialogue of the two principal figures, and the capering dance of the Southern black soldier all are based on the stage caricatures of blacks presented by (mostly white) actors wearing burnt-cork makeup in the minstrel shows popular during the mid-nineteenth century, some of which had toured to London.

The cartoon’s subcaption is a play on the old English proverb “When Greek meets Greek, then comes the tug of war,” a way of describing a situation in which two sides are so equally matched that neither is likely to prevail. Its use is documented as far back as the seventeenth century, and it had been quoted by the popular novelist Anthony Trollope as a chapter title in Doctor Thorne, published a few years prior to the Civil War in 1858.

African Americans in the Tenniel Cartoons

Black Americans appear in twelve of the cartoons. Tenniel tends to treat them in a condescending, stereotypic manner. In his own time such images were doubtless regarded as humorous; the modern reader is more likely to see them as examples of blatant racism. Southern slaves are typically shown wearing simple white cotton work shirts and short trousers, and are usually barefoot [601201; 610119;650506]. Free Northern blacks are sometimes differentiated by their better-dressed appearance, including long trousers and shoes [620809; 630808]. Blacks (always male) are alternatively the hapless victims of oppression by the Southern slavocracy [610119], the dupes of Lincoln and his Black Republican cronies [620809, 630124], or gleeful observers of the white man’s cataclysmic war [610518;620913]. Tenniel and his contemporary British audience seem a bit too eager to dismiss out of hand the notion that blacks themselves had the capacity to be good soldiers, willing to fight and die for their freedom [630926; 641119] — perhaps because of concerns about the possible implications of such a radical idea for the future of their own Anglo-Saxon Empire’s dominion over darker-skinned people around the world.

The cartoons’ captions and text balloons often contain examples of pseudo-black dialect speech. While the intent is humorous, it also serves as a way to underscore the presumed social and intellectual gulf between the childlike, uneducated African American and Punch‘s sophisticated, urbane, upper-class readers. It is unlikely that Tenniel and his colleagues were familiar with actual black speech. As an avid patron of the theatre, Tenniel may have attended performances by American minstrel troupes, some of which had toured to London. In these shows, white actors in burnt-cork blackface makeup parodied the “characteristic” language, music, and dancing of blacks (who in many American cities were not themselves permitted to appear on stage). From the vantage of hindsight, we can see today that the minstrel shows allowed the dominant white culture to use humor to depersonalize blacks and perpetuate stereotypes of racial inferiority.

Scene From the American “Tempest.”Punch, Volume 44, January 24, 1863, p. 35

In Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, the misshapen slave Caliban is promised his freedom by a pair of drunken rogues, Stephano and Trinculo. Although they desire only to use the gullible Caliban to accomplish their own selfish ends, they gain his trust by feigning friendship and equality. In Act III, Scene 2, they gleefully plot with him to take vengeance on his master, Prospero, by destroying his property, murdering him, and ravishing his daughter.

Many in the South feared that newly emancipated slaves would violently turn upon their erstwhile masters. Apparently these fears were also shared by some in England. Here, Lincoln stands in for Stephano and Trinculo, handing a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation to a slave and giving tacit approval to the black man’s desire to take revenge upon his former oppressor.

speaking of abraham lincoln

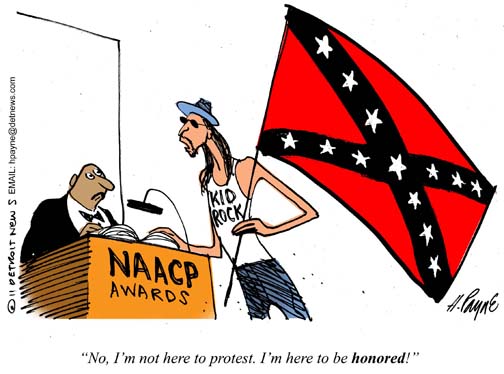

speaking of the confederate flag

ok, so, i like kid rock a little bit. for three reasons: 1. he’s from detroit (well, Michigan anyway) 2. i think his song Amen is brilliant and beautiful 3. he has a biracial son (is that, like, racist of me…or some kind of positive prejudice…or just silly?)

anywho, i do not like his use of the confederate flag. to be fair, i don’t like anyone’s use of it. especially if the user has a child of some significant color. i understand that to some people the flag is simply a symbol of “southern pride.” i really do believe that said people do not view the flag as a pro-slavery emblem… they don’t go around looking at black people wishing they were allowed to own them. that’s too easy, too “obvious racist bad-guy.” but, i think it is from a vantage point of either white privilege or ignorance (or both) that one can insistently be so insensitive as to say (or infer) “i know that this flag is hurtful to many, it reminds them of a time when they were considered less than human and were treated no better than cattle, it may make them feel unsafe…they may get the idea that i think back on those days as the good old days and wish we could revert back to them.” i’m sorry, but the flag is just not THAT cool, not worth all of that. nothing is. i would like to believe that it would be an easy “sacrifice” to put that flag away (as in not on your car, belt buckle, t-shirt…but whatever you want in your own home…) so as not to bring up all of that hateful, hurtful stuff to the people who are still negatively affected by the history of the flag, the implications of it. how about a little more love, compassion, sensitivity… amen.

i mean, this is really not that much cooler than this….

i mean, this is really not that much cooler than this….

not enough to warrant offending people to their core… even if it’s only 14 people, even one… especially if the one might be your kid, Kid.

not enough to warrant offending people to their core… even if it’s only 14 people, even one… especially if the one might be your kid, Kid.

Kid Rock’s NAACP Award Protested Over Use Of Confederate Flag

Some people don’t think Kid Rock is meeting their great expectations.

The rocker is set to accept the NAACP’s Detroit chapter’s Great Expectations Award at their annual Freedom Fund dinner in May, and some members of the historic black rights organization are so unhappy about it, they’re boycotting the 10,000 person affair.

It’s the singer’s use of the Confederate flag in his stage shows that has them so upset, according to the Detroit News.

“It’s a slap in the face for anyone who fought for civil rights in this country,” Adolph Mongo, head of Detroiters for Progress and a boycotting NAACP member told the paper last week. “It’s a symbol of hatred and bigotry.”

For his part, Rock defended the use of the flag in a 2008 interview with the Guardian. “Why should someone be able to own any image and say what it is?” he said. “Sure, it’s definitely got some scars, but I’ve never had an issue with it. To me it just represents pride in southern rock’n’roll music, plus it just looks cool.”

He also spoke about touring with a famed rapper and how it impacted his audience.

“I’ve got Rev Run [from Run DMC] on tour with me right now – we have fun trying to count the number of black people every night. We’re like, ‘There’s 14 tonight, yeah!'”

Though he was a staunch defender of President George W. Bush, the singer went to back for Barack Obama after his election, in the process defending America against accusations of racism.

“It’s good the U.S. has proved it’s not as racist as it’s sometimes portrayed,” he told Metro UK (via Spin Magazine).

He also spoke about his own experience growing up with black people in the interview, saying, “Black people were kind to me growing up and taught me hip-hop and the blues.”

For more on the NAACP controversy, click over to the Detroit News.